Welcome to essays on The Civil War within Illinois.

While the soldiers were fighting for the Union in other states, others were grappling with the Civil War’s effects in their homes, neighborhoods, towns, counties, and the regions within Illinois. Citizens’ preferences and opinions – socially, politically, economically, morally – came into sharper focus and harsher contrasts. While Illinois was not a Civil War battle state, both soldiers and citizens died within Illinois as a consequence of their convictions relative to the national conflict.

The essay immediately below (part 1.1) provides an overview of The Civil War within Illinois, including its scope, topics, and a few of the outcomes. Additional essays will explore the topics in more detail. As always, thank you for reading. —Mark Flotow

The Civil War within Illinois – part 1.1

With a few notable exceptions, the American Civil War was fought primarily in the Southern states, with especially Virginia and Tennessee having witnessed many pitched battles. Most of the Northern states’ citizenry never experienced a Confederate army inside of their borders. Illinois was one of those states, even though at its southern tip the town of Cairo was considered a key strategic point, at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, early in the war. Within days after the fall of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, and President Lincoln’s call for soldiers from all loyal states to defend and preserve the Union, a hastily assembled militia group was sped by rail from bustling Chicago to the sleepier river town. A combination of fears, both real and vividly imagined (particularly in the press), spurred Illinois’s leadership to militarily secure and gradually fortify this small parcel of land for the good of the nation.

Perhaps this was as close as Illinois ever was to becoming a Civil War battle state. However, Illinois and the other Northern states struggled with the Civil War in a number of other ways: economically, politically, socially, morally, and of course, militarily. Within Illinois there were shots fired in anger resulting in both military and civilian deaths, directly and indirectly due to the war itself. For example, the so-called Charleston Riot in Illinois’s Coles County resulted in several violent deaths and others wounded within just a few minutes of spirited fighting with firearms. There were many other recorded incidents of similar war-related bloodshed, although often less of a melee than was the incident at Charleston. In addition, Illinoisans remained wary of skirmishes and battles in the neighboring Civil War “border” states of Missouri and Kentucky spilling over from across the rivers.

Illinois, somewhat like the nation as a whole, was divided politically, economically, and socially before the outbreak of the war. The same might be said for Illinois today. Then, as now, those differences were sources of preferences, pride, and social prejudices, but never rising to the level of legal disassociation or disunion.[1] However, the Civil War stirred the pot of people’s convictions more vigorously than it ever had been before or since. Allegiances and loyalties were tested and strained. Talk and actions about the larger course of the nation came to “shut up or put up,” to state it bluntly. Undercurrents abounded. An early nineteenth century expression was “the devil likes to fish in muddy waters.” In other words, chaos breeds opportunities for mischief and malfeasance that would not occur otherwise.

Inside Illinois, within those murky waters, were robberies and murders, secret societies and organized gangs of outlaws, and the overt machinations of opposing political extremes. To counter those, in some cases, were the military authorities. Illinois became its own official military district, mainly to quell the lawlessness. Yet the state’s military actions never did result in comfortably controlling it.

The soldiers themselves were sources of bloodshed both amongst themselves and against the citizenry, all within the state. Illinois’s citizens could alternate between adoring and scarcely tolerating their own soldiers wherever the latter were encamped or congregated. The soldiers became another dimension of society hardly known inside the state prior to April 1861.[2] Virtually all of these new volunteer soldiers had been Illinois citizens. Yet that did not deter some of them from killing and being killed, and sometimes without having ever left the state. They were trained to fight, so fight they did occasionally, far from the Civil War battlefields. Misbehaviors sometimes escalated to actions against civilians, and sometimes gotten away with, without civil justice being served.

During the war, thousands of Confederate soldiers came to reside in Illinois as prisoners. Illinois, which housed at least its share, was one of several Northern states that had sizeable POW populations during various periods of the war. In too many cases, some of those prisoners died and were buried in Illinois. Prisoners also escaped, sometimes finding sympathetic citizens that helped them flee the state. Many POWs were eventually exchanged or otherwise released to the Confederacy before the end of the war. A relatively small number became “galvanized Yankees” by agreeing to join the Union army. The rest of the surviving POWs were released after the termination of the war. However, these sweeping statements obscure the differences among the state’s POW confinement camps. These were usually make-do facilities to address the sudden surges of Confederate prisoners, starting after the capitulations of forts Henry and Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862, to Illinois general U. S. Grant’s expeditionary forces.

The war’s uncertainties tended to generate endless rumors and fictional intrigues throughout the states, including Cairo being ripe to fall to the Confederates. Among the grandest involving Illinois was the “Northwest Conspiracy” that blended busting out Confederate POWs, such as from Camp Douglas near Chicago, and somehow arming them, perhaps aided by the city’s Southern loyalists, and all timed to disrupt the election process late in the war.

Much more concretely, many Illinois citizens had family members, friends, and neighbors who were in the military.[3] While some Illinois soldiers tried to assist or manage home affairs from afar, more often it was the spouse or other nuclear or extended family members (and sometimes with additional neighborly help) who tended to a farm or business as best they could. Many soldiers sent money home, but that did not replace the lost manpower. Nor did letters – the next best thing to being there during the Civil War era – always help with emotional support, raising children, ameliorating at-home illnesses or accidents, or a myriad of other situational needs that could almost be taken for granted otherwise. And too often, the soldier who returned home was not quite the same person prior to the war, physically and/or emotionally. All of the states struggled both during and after the war administering and aiding the surviving soldiers, widows, and orphaned children.

Although a very small Illinois minority by legislative and policy design, African-Americans were at best marginal members in pre-war society.[4] Although Illinois narrowly remained a free (i.e., non-slavery) state by denying an 1824 proposal for a new constitution that likely would have allowed slavery, legislators subsequently passed the harsh “An Act to prevent the immigration of free Negroes into this State” (more popularly called the “Black Code”) in 1853 and other restrictive statutes. In addition, the national Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was enthusiastically enforced in Illinois. Thus, free Illinois African-Americans were mostly free in name only. The Civil War and the issuance of the president’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 (and the Union winning the war in 1865) changed what freedom meant for African-Americans.[5] How most white Illinoisans felt morally and socially about the change in African-American status, however, proved slower to evolve.

Illinois politics came into sharper focus during the war. After the fall of Fort Sumter, Governor Yates found himself suddenly in a position to initially direct the state’s military arrangements and raise Illinois regiments, somewhat akin to President Lincoln’s authority at the national level. Even though Yates was often energetic and earned the sobriquet of “the soldier’s friend” during the war, he faced political headwinds throughout his full constitutional term, which ended in 1864. Before and during the war, Illinois was almost evenly divided between Democrat and Republican voters, recalling that both Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas were prime candidates in the 1860 presidential election. Nor were each of the two major political parties in Illinois of one stripe. There were pro-war and anti-war Democrats, and slavery abolitionists and anti-abolitionists among the Republicans, with shades in between, all of which surged and receded in numbers and conviction during the war years. Such political struggles severely tested the strength of society’s fabric and, in some cases, it frayed and tattered, much like many of Illinois’s Civil War-scarred regimental flags.

[1] Curiously, in more recent Illinois history, there have been several, mainly politically-motivated attempts by counties or regions to petition or otherwise officially disassociate itself from the rest of state. See David Joens . . .

[2] Illinois had previously raised six regiments for the Mexican War.

[3] There are verified instances of Illinois citizens who went south and joined the Confederate military. However, those numbers are very small and perhaps represent less than a hundred individuals. The true number of enrolled soldiers may be higher, but likely not by much and constituted a relative drop-in-the-bucket within the Confederacy’s armies, despite parts of especially southern Illinois having Southern sympathies.

[4] Before the start of the Civil War, there were less than 8,000 Illinoisans of African-American descent, or about 0.45 percent of the total Illinois population of 1,711,951, based on the 1860 U.S. Census.

[5] Illinois’s Black Codes were repealed in 1865.

The Civil War Within Illinois – part 1.2 – “Introduction”

All of the above and more were part of the Civil War within Illinois. Among the relevant historiography, national-level works often have fractured Illinois-specific events and experiences.[1] On the other hand, Illinois-specific articles, for example, often focus on a singular event, either couched as part of a trend or a one-time occurrence. My purpose for writing this book is to provide a more structured, integrated presentation of the Illinois home-front that gives the reader a sense of how daily lives and society were impacted in numerous ways by the ongoing Civil War. Plus, Illinois’s Civil War narrative is more varied than what most readers might realize. Unsurprisingly, Illinois certainly was not composed of like-minded people with similar backgrounds. Rather, it was its own melting pot within the nation.

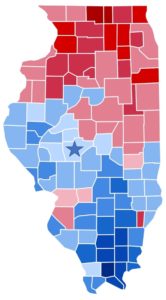

For example, the Civil War-era socio-political dynamics within Illinois were uneven across the state. While the 1860 presidential election results by party for Illinois counties are only a proxy for these differences, it is a reasonable place to start. Figure 1 shows the counties that Douglas carried in the 1860 election (blue) and those that Lincoln won (red).[2] Lighter hues indicate narrower victories. It is interesting to note that Lincoln did not carry his adopted-home county, Sangamon (with star), which features the capital of Illinois (Springfield). The Republican voters had the majorities in the northern part of the state and the Democratic had the majorities in the southern portion (with a few exceptions), which was somewhat unique to Illinois. For example, two of the other former Northwest Territory states, Indiana and Ohio, had patchwork-like clumps of party-favoring counties in regard to the 1860 election. Illinois, had been initially settled as a territory in its southern portions and primarily by former Southerners (e.g., from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia). In 1818, as a territory just before statehood, Illinois had fifteen counties: twelve in its southern one-quarter and just three, vertically-expansive counties that

Figure 1. 1860 presidential election results for Illinois counties; blue = Democratic majority; red = Republican majority.

stretched to what became the Illinois/Wisconsin border.[3] Illinois’s first territorial and state capital was Kaskaskia, about 70 miles south of St. Louis, on the Mississippi River. Once Illinois achieved statehood, migrants from the northeastern part of the nation, such as New York and Massachusetts, began settling particularly in the northern part of the state. These constituted the primary population streams into Illinois, with the southern settlers more accustomed to southern lifeways (including slavery) and voting Democratic, and the northern in-migrants preferring the New England states’ customs and voting for political parties other than Democrat (e.g., Whig, Free Soil, and later, Republican). Bear in mind, this was how the majority of those casting votes favored one party over another, geographically, but with plenty of exceptions that regionally produced thinner margins. As an example, going back to the 1860 presidential election in Sangamon County, 48.9 percent voted for Democrat Douglas, 48.3 percent voted for Republican Lincoln, and 2.8 percent voted for other candidates. The total for Douglas was 3,598 and Lincoln garnered 3,556, which is a mere 42-vote difference.[4]

Despite southern Illinois initially having the most population at the time of statehood, by 1860 Chicago was by far the state’s largest city, with 109,260 residents.[5] The next largest cities were Peoria (14,045), Quincy (13,718), Springfield (9,320), and Galena (8,196). However, Illinois was still very much an agrarian state, and Chicagoans represented less than 6.5 percent of the state’s total population of 1,711,951.[6] In 1860, about half of Chicagoans were foreign-born. For the state as a whole, including Chicago, 19 percent were foreign-born. Near the beginning of the Civil War, Chicago attracted large numbers of immigrants, especially from Germany and Ireland, searching for non-agrarian employment. Thus, in a number of ways, Chicago was demographically different from the rest of Illinois.

The demographics of Illinois’s Civil War soldiers reflect some of the state’s 1860 population characteristics. Data were collected by the military at the time of enlistment or commission, such as height, eye and hair color. More germane to census data, also collected were age, place of birth, marital status, and previous occupation, among others. Based on a random sample from this database, the median age of the soldiers was 23 years.[7] Two aspects that support the sample’s general representativeness of almost 300,000 Civil War soldiers is that 90 of the 102 Illinois counties are present, and the soldiers’ ranks are roughly in proportion of what one would find in an infantry regiment.[8]

The soldiers born in Illinois were in the decided minority, at 26 percent. Other state origins were New York (10%), Ohio (10%) and Indiana (7%) as the three largest. Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee each came in at about 5 percent. Of note, 16 percent were foreign-born, with Germany (6%), England (3%), Ireland (2%), and Canada (2%) as the leading countries of origin. For those in this sample that had a stated marital status, 29 percent were married and 71 percent were single. Many of the single soldiers tended to be younger, not surprisingly. By far and away, “farmer” was the largest result in the occupation category, at 67 percent or about two-thirds of the soldiers in the sample. Bear in mind that farmer may have been a catch-all category. That is, it did not mean the person was the farm owner or it could apply to someone working at a farm of another family. It also did not distinguish among farm sizes, the crops or vegetables grown, or if the person was an overseer only and not a farm laborer. Other occupations stated, which were generally more specific categories, included carpenter (4%), clerk (2%), blacksmith (2%), printer (1%), student (1%), and shoemaker (1%), among others.[9] Like some other Northern states, Illinois’s soldiers were not nearly all from agricultural backgrounds, unmarried, or even originally from Illinois.

[1] For example, Daniel E. Sutherland’s A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009) does well in examining the various shades and degrees of guerrilla warfare, but the nature of it in Illinois is only scratched on the surface, contrasted with its relative ubiquity among the Southern and some of the border states.

[2] Figure 1 was adapted from and courtesy of Tyler Kutschbach (1 April 2021) through the Creative Commons, Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

[3] Jesse White, Illinois Secretary of State, Origin and Evolution of Illinois Counties, reprint (Springfield: State of Illinois, 2010), 35. This booklet features a series of maps that mirror the American settlement of Illinois.

[4] See John Moses, Illinois: Historical and Statistical, 2 volumes (Chicago: Fergus Printing, 1895), 2:1208–9, for 1860 voting by county.

[5] Already by 1850, Chicago was Illinois’s largest city with a population of 29,963.

[6] For comparison, based on the 2020 U.S. Census, Chicago residents represented over 21 percent of the state’s population.

[7] This information was derived from the Illinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls database, Office of the Illinois Secretary of State, available online, using a random sample size of three hundred. Other drawn samples may produce different results. See https://www.ilsos.gov/departments/archives/databases/datcivil.html I previously have calculated median age for all Union soldiers to be about 23.75 years, derived from data in Benjamin Apthorp Gould, Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldiers (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1869), 34.

[8] A regiment at full strength would have about 1,000 soldiers and officers. There would be about nine regimental-level officers (such as colonel and quartermaster) and comprise about 1 percent of the regiment’s personnel. Similarly, within the collective of companies would be captains and lieutenants (3%), sergeants (2%), corporals (6%), musicians (2%), and privates (86%). The sample’s percentages were 1% for regimental-level officers and staff, 4%, 5%, 6%, 1%, and finally 83% for the privates.

[9] “Laborer” was another catch-all category, at 4 percent.