Questions & Answers

Each week, I will choose a question or comment from readers about Illinois Civil War soldiers. I will do my best, each Friday, to respond to a selected question. I would prefer to answer inquiries directly related to the book or Illinois Civil War soldiers, but I will at least read and consider all reader submissions. Please see the sidebar on how to submit a question for this page. =====>

[NB: for older posts, please see the Older Q of the Week (2019-20) page.]

The 1 July 2022 entry, immediately below, is the last Question of the Week on this website. However, new weekly postings will be appearing on the Civil War within Illinois page of this website. Please click on that page tab for more details. And, as always, thanks for reading.

———————————————————————————————————————

Musket technology (added 1 July 2022)

If the musket was the primary soldier weapon during the Civil War, how much did it change through the course of the war?

Humboldt, Tennessee, November 17, 1862, to father

the boys have to keep there gunes and selvs clean I hant saw but one body louse yet since I left I Weigh 175 pounds and active as and [any] farmer the boys dont truble me and more for they have got a quainted with me my gun shoots 1000 yds I can shoot her where I Want to

—Private John Laingor, 54th Infantry, Shelby County

According to Boatner, anything less than a cannon was considered “small arms” during the Civil War, and that would include muskets.[1] “At the outbreak of the war the Federals had 300,000 smoothbore muskets and 27,000 rifles in the arsenals still in their possession.”[2] Similar to rifled cannons, rifled muskets had a spiral groove to improve the accuracy and distance of a fired projectile, such as a lead bullet from a musket. Smoothbore muskets were part of an earlier era but also were still used during the Civil War, especially during the first year or so.

Mound City, Illinois, December 2, 1861, to brother, David

last sunday in the guard house, three off our soldiers were shot for trying to b[r]eak out. a mistake two Soldiers and one Citizen one Soldier from Company D. got his leg shot so badly that it has to be taken of[f] he was shot between the knee and ankle joint. a fellow from our Company had two buck shot in you know what. he is not seriously wounded and will be well in a few days. the Citizen was shot with a musket directly through the knee joint and his leg and is shivered all to pieces his leg was taken off imediately and it is though[t] that it will kill him.

—Private James Swales, 10th Infantry, Morgan County

In Private Swales’s letter, the soldier who “had two buck shot in you know what” (maybe in his “arse”) implies that he was shot with a smoothbore musket. Often, such muskets were loaded with a cartridge containing black powder, paper (i.e., the cartridge container), a lead ball, and a few smaller balls of buckshot. This was often called “buck and ball.” The buckshot would spread when shot, somewhat like from a shotgun, increasing the odds of hitting a target, say within a phalanx of advancing enemy infantry soldiers. Smoothbores were especially lethal within 200 yards but, beyond that, the buckshot lost too much velocity to be effective.

ten miles from Atlanta, Georgia, July 7, 1864, to friend, Lizzie Wilson

I know my letters, are few and poorly written but I can do no better when in the rifle pits with the rebels picking away at me with “minnies”

—Corporal James Crawford, 80th Infantry, Randolph County

To take advantage of rifled muskets, the ball or bullet that became common in the Civil War was the Minié ball, named after its French inventor. (Civil War soldiers often referred to them as a “minie” or “minnie,” as Corporal Crawford did.) The Minié ball was made of soft lead and had a conical shape. When the ball was loaded and fired, the lead expanded into the spiral-rifled barrel. Thus, the Minié ball could be projected more powerfully and truer than a ball from a smoothbore musket. A Minié ball fired from a rifled musket had an effective range of 300-800 yards.

Springfield, Missouri, November 10, 1862, to “My Dear Adah”

we are to exchange our guns this evening for the Springfield Rifle the guns that we had are not worth much

—Private William McMullen, 94th Infantry, McLean County

Camp Quincy, Illinois, September 19, 1862, to father, Robert D. Taylor

We are armed. equiped ready for marching or battle. We have Enfield Rifles which are good to close 900 yards. Our drill master hit a board the size of a man with one of them. 800 yards and that is good shooting.

—Private Benjamine Taylor, 84th Infantry, McDonough County

Nineteen-year-old Private McMullen clearly saw the advantages of a rifle musket over a smoothbore. Two of the more common Civil War rifled muskets were the Springfield and the British-made Enfield, both which had similar bore diameters. The Springfield rifle musket, made at Springfield, Massachusetts, was about five feet long, weighted nine pounds, and could be fitted with a bayonet. The Enfield was similar and had an effective range of about 1,000 yards. It was popular among both the Union and Confederate soldiers as a small-arms weapon of choice.

Rifled muskets changed the nature of warfare even if it took Civil War generals a while to adjust their tactics accordingly. For example, soldiers advancing over long, open fields were in small-arms range much longer with rifle versus smoothbore muskets (e.g., no waiting to see “the whites of their eyes” before firing).

Gallatin, Tennessee, May 1, 1863, to mother

We were marched on board a train . . . and moved off in the direction of Louisville. After passing Franklin about 27 miles from Gallatin and as we neared a thick growth of woods the train suddenly stopped and bang- bang- bang, went firearms in the woods near by. Quick as lighting a roar of musketry from the boys followed the first fire. . . . The devils had displaced a rail, but the engineer discovered the break in time to stop the train. . . . there were about 35 of them = they were within 20 or 30 feet of the cars. 5 of our Regt were wounded = two mortally—having since died. Also a little drummer boy had his leg shattered by a ball.

—Sergeant Major Stephen Fleharty, 102nd Infantry, Mercer County

An unfortunate consequence was surgeons had to adjust dealing with wounds caused by the soft-lead Minié balls. In a way, they were almost like explosive bullets upon impact with human bodies. They tended to shatter bone and shred flesh and muscle, which was more destructive, generally, than being hit with buck and ball from a smoothbore. “Shivered all to pieces” was how Private Swales described it in the second quotation, above. Thus, surgeons often amputated Minié ball-hit mangled limbs as a life-saving measure.

Here was a close call.

Lafayette, Tennessee, February 6, 1863, to sister

I had a very narrow escape yesterday which I will Relate We have to get up at 5 Oclock in the morning and form a line of battle and stack arms, and leave them in line until day light. we had just stacked arms and Recd the order to break Ranks, and I started to go to my tent and as I was passing a stack of guns on the left of the Company I saw that they were falling down I jumped out of the reach of the bayonets. They were falling towards me, and just as they struck the ground, one gun went off. I was not more than six feet from the muzzle. And the ball passed through my left boot leg just at the top. And it took pants lining and all slick and clean off of my knee I took out a piece of my pants about as large as a silver dollar, Right on my knee pan. It was a pretty close call. The surgeon said that if it had hit me there at all I should have had to had my leg amputated. I enclose a piece of my pants that the ball cut out.

—Captain Frederick A. Smith, 15th Infantry, DeKalb County

[1] This is according to Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary, revised edition (New York: Vintage Books/Random House, 1991), 766, which is part of an entry on “small arms of the Civil War.”

[2] Boatner, Dictionary, 767.

———————————————————————————————————————

J. A. C. McCoy update (added 24 June 2022)

An Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library librarian wrote to me that their information about “I. A. C. McCoy” has been updated. In fact, it turns out his first name is James.

This soldier is one of the 165 appearing in my book. Here is my original brief biographical sketch for him.

I. A. C. McCoy (SC2700)

McCoy was working in a ward at a Mound City, Illinois, hospital when he wrote a six-page letter to a “Dear Friend” on April 5, 1864. McCoy most likely was from Illinois or Indiana, as he made reference to both the Copperhead uprising in Charleston (Coles County) and friends in Henryville, Indiana. He complained of “intercostal neuralgia,” which, among other things, affected his writing ability. McCoy also expressed opinions about Abraham Lincoln’s reelection chances and referenced southern Illinois.

I suspected he may have been from Indiana, because he was writing to a friend in Indiana. However, there are many Illinois soldiers with the name of McCoy, so it was possible he may have been one of them. Also, the one letter in the collection was written from Mound City (near Cairo), Illinois.

Further recent research on this small collection (SC2700) by the librarian uncovered that McCoy was indeed from Indiana. His name was discovered to be James A. C. McCoy, a physician, from Clark County, Indiana. This county is in the southern portion of the state and across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. In 1860, it appears that McCoy lived near Henryville, which is in the northern part of Clark County. Both of his parents were from Kentucky, and James was born in Indiana in 1827. He was thirty-four years old in October 1861 when he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in Company D of the 49th Indiana Infantry Regiment. However, about three months later, McCoy became an Assistant Surgeon and subsequently was assigned to the hospital at Mound City, Illinois.

After the war, Dr. McCoy lived in Indianapolis and then later in Washington state, where he practiced medicine. He died of pneumonia in 1898, at age seventy-one years, and was buried at the Tacoma Cemetery in Tacoma, Washington.

My sincere thanks go to the librarian at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library who uncovered this additional information and alerted me about it.

———————————————————————————————————————

Artillery at the Battle of Harpers Ferry (added 17 June 2022)

In your recent postings, you have given some examples of the artillery’s roles at various battles. However, most of them also involved naval artillery. Were there any land battles where field artillery proved to be decisive?

Yes, there is one battle in the first half of the Civil War that particularly comes to mind: the Battle of Harpers Ferry. I have written about it before for Question of the Week (September 2020), where I provided Private Winthrop Allen’s descriptive letter about the battle and the 12th Illinois Cavalry’s subsequent escape from the place. I will provide the Harpers Ferry portion of the letter again, but this time with annotations related to the use of artillery and how it impacted the outcome of the battle.

(What I recall about the letter itself is that Private Allen’s handwriting was exceeding small, likely because he was trying to fit the rather long story of his Harpers Ferry experiences onto a few sheets of letter paper. Private Allen noted he had only one stamp, which may explain why he wrote so diminutively. Here is my transcription of the letter, for better or for worse. Some words simply were nigh impossible to decipher due to his cramped-word writing.)

Greencastle, Pennsylvania, September 17, 1862, to brother-in-law, Mr. William A. Tunnell

[on top of the page, squeezed in . . .] I have but one stamp left and if my friends wish me to write they must send me some for it is not likely they will pay us until matters become more settled G [smudged/illegible; may be his initials or name]

Dear Sir –

I wrote a few lines to father this morning but supposing I should not have time to write full particulars of our Skeddaddle from Martinsburgh [Martinsburg, (West) Virginia, about 20 miles to the northwest of Harpers Ferry] through Harpers Ferry to this place. I closed before I finished and without stopping to tell you how we had to burn all our tents and baggage, our Quartermasters and commissary stores and leave M [Martinsburg] with nothing but ourselves, our horses and wagons (empty) and of our arrival safely at Harpers, for all of which we consider ourselves particularly fortunate I will try to write what took place after our arrival at H [Harpers Ferry] on the eve of the 12th. Being without tents we camped on the open fields within the batteries and after such a hard ride during the day as might be expected we slept soundly The next morning we arose with the sun [and we were] hungry. We having nothing to satisfy it I prepared to take a look at the place and its fortifications — but having but little time to look about, I only passed through and what I write may not be true in every particular. The principal part of the city is situated along the banks of the river, beneath a high bluff. It has but one street which runs the full length of [the] place and principal business of the place in terms of [the] place was mostly kept up by the government at the arsenals which are now in ruins. the Baltimore and Ohio R. R. is also on the virginia side and is built on trestle north over the river. The Chesapake & Ohio Canal follows the mountain on the maryland side. As you are aware the Shenandoah river enters the Potamack here which then passes through the Blue Ridge, and as Jefferson says, it is worth a trip across the Atlantic to see it as seen from the Bolivar H[e]ights it is truly a grand site —. By the junction of thease two rivers there is three hights. the highest is the Maryland [Heights to the northeast] which is some 900 feet above the level[?] of the river the next is the Virginia accross the Shenandoah [It is unclear but he may be referring to the Loudoun Heights to the south of Harpers Ferry.] On the Maryland hights was many intrenchments and Batterries, built on purpose for their it is said that one had a battery of 4 fif[t]y pounder Parrott siege guns and 1 onehundred twenty four in[ch] siege gun besides several field batteries on the side facing the Ferry was a battery of 50 pounder Parrotts which commanded this approach by the river up and down.

[“One of the keys to any defense of Harper’s [sic] Ferry was a powerful battery – two 9-inch naval Dahlgren rifles,[1] one 50-pounder Parrott rifle, and four 12-pounder smoothbores – halfway up the heights and sited to cover the approaches to the town from the south and west.”][2]

but the principal deffences were on the Bolivar hights [to the west] in view of the Ferry — here was three battries consisting of about 40 guns connected by intrenchments and rifle pits. thease were on the virginia side and considered impregnable.

The morning after our arrival we found that we had quit one besieged place only to fall into another. for it was found late at night that the enemy had followed us from M [Martinsburg] and now the place was blockaded on all sides, and were preparing to attack our batteries on the Maryland hights At about 6 oclock a. m. on the 13th the attack commenced and was continued until about noon when our men gave way and fled, having spiked [i.e., ruined] the guns and crossed over the Ferry —

[Sears describes “when our men gave way” in the following passage. The 126th New York Infantry had been in the service for three weeks. They were ordered to the crest of Maryland Heights to fend off two Confederate brigades coming from the north (the back of Maryland Heights). “The battle opened with a spatter of skirmishing fire, and the Yankee pickets came running back, shouting the alarm. Suddenly there was a crash of heavy volleys and the unnerving sound of Rebel yells . . . The rookies of the 126th had not imagined it would be anything like this, facing unseen foes . . . who seemed to know a great deal more about fighting than they did.” They tried to form a battleline at their breastworks behind them. The Confederates “delivered another withering volley, and one of the bullets caught [the 126th’s] Colonel Sherrill in the face, inflicting a ghastly wound. Seeing their colonel writhing on the ground was too much for the green troops, and the 126th broke again, this time in complete rout.”][3]

we still had possession of the battery of 50 pounders facing the Ferry and the enemy was shelled during the afternoon at intervals until dark. When the firing ceased and thing[s] wore a gloomy aspect, for it was known sinc[e] that if then [the] enemy had any heavy guns they would be placed on the maryland hights. the key to the whole position, and we could not dislodge them – also that they could place their batteries on the virginia hights [Loudoun Heights] without from of b[e]ing disturbed, and our fears proved true for the next morning found the rebels busily engaged erecting a battery on the Virginia hights –

[Confederate general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson sent two brigades that “arrived at the foot of Loudoun Heights. His patrols cautiously made their way up the slope and to their surprise found the crest unoccupied. Of the three areas of high ground commanding Harper’s [sic] Ferry, only Bolivar Heights now remained in Federal hands.”][4]

Our batteries began playing on them at an early hour the next morning but could not effect much b[e]ing constructed almost altogether for deffense in the other direction. The enemy kept displaying signals during the afternoon, and at about 12 they opened upon us. the first shell came right into our camp and produced quite a panic among both horses and men – the latter having unsaddled – and men preparing to eat dinner, but fortunately did not burst the next horror bursted, and covered several of the boys with dirt and dust and killing a horse of one of the other companies but you may depend there was no waiting for orders then. some saddled some left without horses, arms, or any thing and all ran for the trenches for dear life, The shells following thick and fast, whiz, burn[?] burst, and blubbers It was laffable after it was over but pretty serious while on hand The boys all declaring they had rather face “double grand thunder and lightening” than those shells from this time they kept up a severe fire upon our [cannon?] batteries until five oclock when their fire slackened and at last ceased when it was found that they were advancing on both flanks Towards the Batteries on Bolivar heights after some pretty severe skirmish fighting the enemy appeared in battle order advancing in great [numbers?] upon our left but were repulsed almost as soon as they appeared in sight by the fire of our infantry and artillery it is supposed with considerable loss In the meantime their whole line advanced within a mile and a half of our works and then they stoped and the firing ceased for the night The cavalry forces being of no use in defending the place it was determined [that on September 14] about sun down that they should leave and accordingly at about 8 o’clock they were all assembled at the ferry with no baggage, ambulances, sick &c. to encumber them prepared to cut their way out if necessary to a safer place, especially as it had been determined that, if the enemy planted batteries on the Heights, to surrender the place next morning

—Private Winthrop Allen, 12th Cavalry, Greene County

And that was what pretty much was happened the next day, on 15 September. At the “break of day . . . the quiet was shattered by a tremendous bombardment, the thunder of the guns reverberating through the valleys. The Rebel batteries on Maryland Heights and Loundoun Heights poured in shells from above, but the heaviest and most destructive cannonading came from Jackson’s guns taking the Federal lines on Bolivar Heights under fire from front, flank, and rear. The return fire was erratic and ineffective, and sputtered out shortly before eight o’clock. Jackson’s infantry was preparing to storm the works when a horseman appeared within the lines, waving a white flag.”[5]

In this engagement, the Confederate field artillery that had been maneuvered onto the heights overlooking Harpers Ferry made all the difference in subduing the Union defenders, and Jackson’s infantry was spared the trouble of having to make an assault.

Overall, the loss of Harpers Ferry was a Union embarrassment due to a poor defense (albeit in a tough place to defend) led by Colonel Dixon S. Miles, a Mexican War veteran, and it was a grand accomplishment for General Jackson’s Confederates. There were roughly 12,000 Union soldiers made prisoners. From Harpers Ferry, Jackson rushed his troops to join the battle at Antietam on 17 September.

[1] Dahlgren guns were rifled cannons and primarily used by the navy. They had a distinctive “soda bottle” barrel profile and were designed to have the most metal where the gun produced the most pressure while firing. Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary, revised edition (New York: Vintage Books/Random House, 1991), 218. However, like at Harpers Ferry, some Dahlgren guns were used by land-based artillery batteries.

[2] Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (Boston: Mariner Books, 1983), 122.

[3] Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 123.

[4] Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 124.

[5] Sears, Landscape Turned Red, 152-53.

———————————————————————————————————————

Civil War weaponry: artillery (part 2) (added 10 June 2022)

In your book, there is a letter quotation regarding the Battle of Shiloh that mentions “mangled by our grape & cannister shot.” Was that fired from cannons? What other sorts of projectiles were shot from Civil War cannons?

In this post, I will describe some of the cannons that shot the larger projectiles during the Civil War. My intention is to focus mainly on field artillery.

[I need to preface my response with a caveat: I am far from being any kind of Civil War weaponry expert and likely never will be. In fact, the only thing I can think of currently on my bookshelves that might be of use here is Boatner’s Civil War dictionary. Thus, much of my response will come from some of its pages.[1]]

“My War Experience,” presented April 12, 1888, in Chicago, Illinois, at a veteran reunion

“our” Battery, consisted of four twelve pound Napoleon guns, brass pieces, and two ten pound steel parrott guns

—Lewis Lake, former private, 1st Light Artillery, Winnebago County

The 12-pound smoothbore, muzzle-loaded Napoleon cannon was “the basic artillery piece of the war, on both sides.”[2] Technically, there are three basic types of cannons: mortars (that fire a high arcing projectile), “guns” (with a relatively flat trajectory), and a howitzer (with a trajectory between mortars and guns). The Napoleon is considered a howitzer. Most Napoleons’ barrels were cast of brass. Its maximum range was a little over 1,500 yards, “but its maximum effective range was between 800 and 1,000 yards.”[3] It could shoot all the various types of shot I had described in part 1 (i.e., last week’s posting). It could be particularly lethal at close range.

“The standard field artillery pieces of the Civil War, used on both sides, were: the 6- and 12-pounder guns; the 12-, 24- and 32-pounder howitzers; the 12-pounder mountain howitzer; the 12-pounder Napoleon gun howitzer; the 10- and 20-pounder Parrott rifles; and the 3-inch Ordnance gun. All of these were muzzle-loaders.”[4] The rifled cannons were “constructed with spiral grooves to spin its projectile and give it a more accurate flight.”[5] (Both cannons and muskets could have spiral-rifled barrels. “Rifle,” here, is not to be confused with its more common meaning of “a weapon fired from the shoulder.”)[6]

Parrott rifles were an example of the cast iron artillery pieces, which were far less numerous than the various brass ones (especially among the Union batteries). “To make a gun barrel strong enough to withstand the greater pressures required in rifled artillery, Parrott’s system was to heat shrink a heavy wrought-iron band around the breech, where the pressures were greatest.”[7] Some Parrott rifles had a range of about two miles. However, they were not always popular among the artillerists as the barrels could burst from firing. They also were heavier than most artillery, requiring eight horses to transport them, versus six horses for the more ubiquitous Napoleon pieces.

Mortars were a somewhat different sort of artillery, used to lob explosive shells into an enemy position, such as a fortress. Generally, mortars were used as siege weapons. Here is an example describing mortars used at the siege of Fort Morgan, near the mouth of Mobile Bay, Alabama.

Fort Morgan, Alabama, August 18, 1864, to wife, Ruth

our men are working day and night putting up heavy guns in full view of the rebel fort [Morgan] . . . it is a very strong place, we have got them entirely surrounded[8]

—Private Almon Morrow, 94th Infantry, McLean County

Private Morrow wrote again a few days later: “the General says when we get all the big guns ready to operate we can listen to the music, we have heard enough now to remind us of [the siege of] Vicksburg.”[9] On 22 August 1864, the bombardment began. “Once the mortars acquired the range, nearly every shell landed within the fort . . . The batteries cease[d] firing at night but the mortars continued and about 9pm a fierce fire broke out inside the fort burning the citadel and barracks.”[10]

Mobile Point, Alabama, August 23, 1864

The army and navy batteries . . . opened on the fort [Morgan] yesterday morning, since which time the enemy have not been able to fire a shot from a heavy gun, so completely were they silenced. . . . Much of the property inside the Fort has been destroyed by our mortar shells, the buildings inside being mostly burned or still burning.[11]

—from “Mac” and printed in the Bloomington Pantagraph, September 12, 1864, presumably written by a soldier from the 94th Infantry, McLean County

Finally, here is a description of an artillery bombardment at the Battle of Island No. 10, near southern Missouri, on the Mississippi River (28 February to 8 April 1862). There was a steady bombardment by the Union ships during this period by cannons on gunboats and especially mortars on rafts.

camp near New Madrid, Missouri, March 25, 1862, to wife, Sarah

We arrived here a week ago Last Sunday & found all Quiet when we Got here. the Battle had been fought & the Town Evacuated when we arrived. altho it was not much of a Battle they were Bombarding for four days & the fifth day they Evacuated the place & took Refuge on Island No 10, where they Commenced fortifying & as soon as our Comodore found it Out went down with his Gun Boats & mortars from Cairo & Commenced Shelling & harrassing them so that they Could not make much head way at fortifying. but our mortars kept Constantly Shelling them them there [?] until they were Compelled to advance with a flag of truce to our Lines & Beg of us to hold on until they could Bury their Dead, & one of our men that was a witness to the Scene Says the Ground there was Literally Strewn with Dead bodys, an awful Sight to behold. But all this time our Gun Boats Lay out of reach of them & we played on them with our Largest mortars & Lay out of their reach. unfortunately one of our Large Guns Bursted & killed one man & wounded Several more. . . .

our Doctor & Steward Quarters down near our Camp & Comes up Night & morning to the Hospittle which is a farm house & the Steward Said when he was up this morning that there was Some talk of a Battle today down to Point Pleasant about twenty miles Down the River from New Madrid where our men are Stationed with an Efficient Siege Battery to Stop Rebel Gun Boats from passing up the river. the Guns were sent down there Since we arrived here, & when the men were mounting the first Gun a (32 pounder) three Rebel Gun Boats hove in Sight & before they Got the Gun mounted the Boats Came up & opened a fire upon them, & our men ranged the Gun that they were at work at & Braced it up as well as they Could, Loaded & returned their fire & kept firing until they Sank one of the Boats & disabled the other two & they two put back down the river

—Private David Gregg, 1st Light Artillery, LaSalle County

[1] Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary, revised edition (New York: Vintage Books/Random House, 1991). There is a main entry titled “Cannon of the Civil War” but also more specific entries, such as “Canister” and “Parrott Gun.”

[2] Boatner, 119.

[3] Boatner, 578.

[4] Boatner, 120.

[5] Boatner, 700.

[6] If you would like to see images of some of these artillery pieces, this link is not a bad place to start: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Field_artillery_in_the_American_Civil_War

[7] Boatner, 621.

[8] Letter transcription from William Iseminger, From McLean to Mobile: A History of the 94th Illinois Infantry Regiment Volunteers, 1862-1864, “The McLean Regiment” (Columbia, SC [IL?]: publisher not identified, 2022), 190.

[9] Iseminger, 94th Illinois, 191; letter from Almon Morrow to wife, Ruth, August 22, 1864.

[10] Iseminger, 94th Illinois, 191.

[11] Iseminger, 94th Illinois, 191.

———————————————————————————————————————

Civil War weaponry: artillery (part 1) (added 3 June 2022)

In your book, there is a letter quotation regarding the Battle of Shiloh that mentions “mangled by our grape & cannister shot.” Was that fired from cannons? What other sorts of projectiles were shot from Civil War cannons?

I need to preface my response with a caveat: I am far from being any kind of Civil War weaponry expert and likely never will be. In fact, the only thing I can think of currently on my bookshelves that might be of use here is Boatner’s Civil War dictionary. Thus, much of my response will come from some of its pages.[1]

Camp Morgan, Mound City, Illinois, October 9, 1861, to brother, Dave

who thinks of the horrors of the Battle field and does not flinch at the thoughts of it the Bravest of the Brave will do it in spite of there heroism the man never drawed the sweet breath of life that could face the cannon mouth without flinching from it. they can boast and brag all they will but let them try it on once and if they dont get up and howl, I will treat to the lager beer, aint that fair?

—Private James Swales, 10th Infantry, Morgan County

What roared from the mouths of cannons was certainly worth flinching from! The typical Civil War smoothbore battlefield cannon could shoot canister, “grape,” and solid shot (listed from smallest projectile to largest).

Camp McClernand at Cairo, Illinois, November 10, 1861, to wife, Diza

[in describing the Battle of Belmont, Missouri] often was when the bullets flew like hail, and the grape and canister shot tearing limbs from the trees – but was unhurt.

—Quartermaster Lindorf Ozburn, 31st Infantry, Jackson County

headquarters of the 93rd Illinois Infantry [probably late 1863, or 1864], to Illinois governor Richard Yates

the [regimental flag]Staff Shattered by a canister shot in the charge of Tunnel Hill Nov. 25, 1863 [part of the Battle of Chattanooga, Tennessee].

—Lieutenant Colonel Nicholas Buswell, 93rd Infantry, Bureau County

Canister shot consisted of “small cast-iron or lead balls (bullets) or long slugs, set in dry sawdust, that scattered immediately on leaving the (cannon’s) muzzle.”[2] The canister part – essentially a tin can of the right diameter or caliber – contained the small metal balls. Canister shot was used as short-range ammunition (most effectively within 100-200 yards) and particularly against an enemy’s approaching infantry. It could have the effect of shredding “limbs from trees” or mangling human bodies. Sometimes in defensive desperation, it was double-loaded and called “double canister.”

“My War Experience,” presented April 12, 1888, in Chicago, Illinois, at a veteran reunion

We returned to the line in time to take position, when [Confederate] General Frank Cheatham[‘]s division massed in our front, came steadily forward – all the while we were giving them double shotted canister.

—Lewis Lake, former private, 1st Light Artillery, Winnebago County

Lake mentioned this in reference to action on 22 July 1864 near Atlanta, Georgia, and just before his battery was surrounded and captured.

Grape shot (or, grapeshot) was “a number of iron balls (usually nine) put together by means of two iron plates, two rings, and an iron pin passing through the top and bottom plates.”[3] In other words, the grape-sized balls were held together in clusters before being shot. It was similar to canister but with fewer and larger projectiles. It also had a further effective range, of about 1,000 yards. Both canister and grape shot were particularly effective against massed infantry. Grape also could be double-shotted.

Luray, Virginia, June 12, 1862, to cousin, Mrs. Theoda S. Fulton

[describing the Battle of Port Republic, Virginia, 9 June 1862] we arrived in due time and planted our Batteries they came on and forced us back and crossed with a large force and mad[e] an attempt to annihilate us – on they came and we though small in number stood fast our Batteries making fearful havoc in their ranks with showers of Grape shot our boys charged and recharged with the Bayonet driving them at all points

—Private Ransom Bedell, 39th Infantry, Cook County

The largest projectiles were single cannonballs (or, solid shot) and shells. Shot contained no explosive or powder. It was used for battering, such as against forts or ships.

onboard steamer Thomas E. Tutt, in Mississippi, January 19, 1863, to mother

[regarding action at Fort Hindman or Arkansas Post] It is really remarkable and unbelievable; however, I have seen it and am convenienced. Of two 100-pounders standing in casemates by the fort (Arkansas Post, which we took), one of the same was pierced in the middle by a cannonball. In other words, 7 or 8 inch thick cast iron was penetrated like a feather. The other was hit on the mouth so that its upper lip dissolved and the whole cannon made a backwards somersault. The casemates still bear many traces of balls. The former consisted of a log house in which the walls as well as the roof were made of 3-foot thick wood faces. Along the front there was a 6-foot thick end wall and the roof was also covered with railroad rails. But the [projectiles] were so effective on the roof and against the sides that they broke through the iron rails a great deal as well as the wooden walls, and probably also delivered the secesh cannoneers quite unpleasant boxes on the ears.

But enough of this. Our gunboats have proven that they are extraordinary machines for destruction and death. If only our “old Abe” had a few more gunboats.

—2nd Lieutenant Henry Kircher, 12th Missouri (Union) Infantry, St. Clair County

In the above, the cannonballs were shot from a ship at a fort. Here is an example from fort to ship.

Cairo, Illinois, April 7, 1864, to friend, Mr. Tailor Ridgway

there was a big boat tried to run by here yesterday with contraband goods on her and our boys got in to the fort and opened a sixty four pound cannon on her and I tell you she bawled they shot at her three times and she came to shore a howling. and they arrested her captain and put him in the guard house. that is what a fellow gets for trying to be a rebel, to his country. there is a great many boats runing now and they are doing a big business.

—Corporal Jeremiah Butcher, 122nd Infantry, Macoupin County

Shells were hollow projectiles containing powder meant to explode via a fuse. The fuse had to be set and the shell would explode while in the air or after hitting the ground, causing the fragmenting shell casing to become shrapnel. However, “this type of projectile was rather ineffective because of poor fuzes [sic] . . . and because the black powder bursting charge did not properly fragment the cast-iron ‘shell.’”[4] Nevertheless, here is an example where the shell properly exploded.

onboard steamer Thomas E. Tutt, in Mississippi, January 3, 1863, to “Dear mother”

[at the battle of Chickasaw Bluffs] But one hollow ball, indeed it was a lucky shot I think, otherwise a master shot, came just as about 6-8 pioneers were sent ahead to move a tree about 30 steps from us away from the levee and had just gotten to the work. It lay on the tree for a moment in the middle of the small party and then sprang open with an explosion that knocked both legs off one of the pioneers and sent them far apart. It injured another severely on the lower body, who will probably also be dead. It wounded a lieutenant who commanded them and also three or four others less severely. A large piece of the shell about a pound in weight buried itself in the head of Charles Becker, cousin of the one who lost his leg near Pea Ridge. He was immediately dead, as the entire upper head was separated from the lower part. Naturally, he was very disfigured, but still his suffering was short or not at all, for he gave no sound, twitched a muscle; better so than mutilated.

—2nd Lieutenant Henry Kircher, 12th Missouri (Union) Infantry, St. Clair County

It is difficult to understand the reasoning for sending such a detailed description to one’s mother of an effective cannon shell shot amidst soldier! It this case, the shell landed while the fuse was still burning and subsequently exploded.

Another type of ammunition was chain shot. This consisted of two balls connected by a chain (or alternatively, connected by a bar). This was “designed for use against masts and rigging of ships.”[5]

I should note that there were nine common calibers for cannons in the Union army regarding the use of canister, grape, solid shot, and shells. I will end with just a few words about specific types of projectiles (of which, Boatner lists ten by name). For example, a Hotchkiss projectile has “three parts: the body, an expanding ring of lead, and a cast-iron cup. The iron cup pushes against the lead ring when the gun is fired, forcing the lead into the rifling of the gun.”[6] Types of cannons, such as those with or without rifling, will be covered in next week’s posting of part 2 about Civil War artillery.

onboard gunboat Romeo, at the Junction of Tallahatchie and Yalobusha rivers, March 17, 1863, to mother

The rolling of [our] cannon thunder, the echo of the same, the hissing of one, the howling of the second, the explosion of the third ball all continued without ceasing until midday. We went to eat and enjoyed our meal while the music sounded.

—2nd Lieutenant Henry Kircher, 12th Missouri (Union) Infantry, St. Clair County

[1] Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary, revised edition (New York: Vintage Books/Random House, 1991). There is a main entry titled “Cannon of the Civil War” but also more specific entries, such as “Canister” and “Parrott Gun.”

[2] Boatner, 119.

[3] Boatner, 354.

[4] Boatner, 738.

[5] Boatner, 135.

[6] Boatner, 411.

———————————————————————————————————————

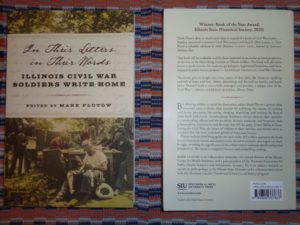

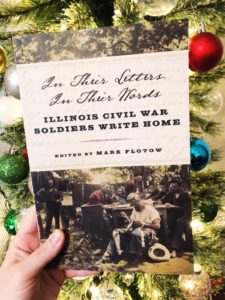

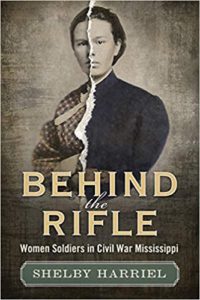

Promoting the book (part 2) (added 27 May 2022)

Since your book came out a few years ago, do you still do book promotions (besides on the website)?

I am going to address this slightly differently than what I wrote in last week’s posting (part 1).

In a real way, I am a partner with the publisher, Southern Illinois University Press, in promoting the book. So, I sometimes team up with them when an opportunity arises. For example, I have been at the SIU Press tables at the Conference for Illinois History on a few occasions to sign books. Or, more recently, I have recorded two podcast segments connected with SIU Press (see a Memorial Day-related example, below). Personally, I believe having and working with a good, reputable publisher is especially important when it comes to promotion. If you partner with a small publisher, or self-publish, then there is a necessity for the author to also be a tireless self-promoter.

I also have done at least three radio promotions (that I can recall) related to the book: one was live and two were prerecorded. (Embarrassingly, I remembered only afterwards that I failed to mention the title of the book during the live broadcast.) In any case, I enjoyed those opportunities to speak to unseen listeners.

In last week’s posting, I mentioned the beer-tasting event where I had a microphone for about ten minutes to say a few words about the book. I used only three prepared Illinois Civil War soldiers’ letter quotations related to beer or alcohol, but I had pre-printed them and gave them to three different attendees to read aloud during those ten minutes.[1] Make no mistake about it: people were there for the alcohol festivities and I was very much a side-show, except for my brief time with the microphone. Nevertheless, I sold ten books that evening, which was all I had brought for the occasion. I like to think those purchases were based on the merit of the book, and less to do with people drinking and having money, but who knows.

Here is a link to a brief Memorial Day-oriented essay that offered an opportunity to mention the book in the ending credits. It happened to be published yesterday (26 May 2022).

https://www.illinoistimes.com/springfield/these-honored-dead/Content?oid=15184302

To sweeten it, the newspaper editor added a generously-large image of the book’s cover. That addition tilts this example towards the ideal end of the promotional spectrum.

As a final example, earlier this month, I was asked by SIU Press to do a brief podcast “spot” for their “Inside the Blanket Fort” as part of Blanket Fort Radio Theater. You can find this series of BFRT podcasts here: https://news.wsiu.org/podcast/inside-the-blanket-fort It likely will be posted on a Thursday in June. The podcast spot has been excerpted from the following 4 January 1866 newspaper article from the Illinois State Journal, published in Springfield. In it, there are strong elements of why there is, now, a national Memorial Day, even though this was written and delivered well before there was a day set aside for regular, organized commemorations dedicated to the Civil War dead. And obviously, the following speech was delivered to soldiers who did not die in the Civil War, yet the author reminds them that the nation has obligations to its past soldiers, both living and sacrificed.

*****

Dinner To The Invalid Soldiers At Camp Butler.—The patients in the hospitals at Camp Butler were the recipients of a sumptuous dinner on New Year’s, provided for them by the surgeons there in charge. It was a very pleasant occasion to all concerned, and the soldiers especially will long retain it in their memories. After the repast, the following address was delivered by Miss Carrie C. McNair, who has had charge of the special diet department of the Camp. Miss McNair has endeared herself to all the patients, and her address was received with every manifestation of respect and affection.

SOLDIERS: I wish you all a happy New Year; and as you are about to return to your homes, to the presence of the dear ones left behind, I pray God to bless you all. And after three long years of weary marches and hasty bivouacks; after standing as a wall of living fire before your country; may you all reap your reward in long, peaceful lives, surrounded by plenty and kind friends.

I know that all these comforts and blessings will be appreciated by these war-worn veterans before me. I think I can share in your anxiety to “get home” and mingle once more in the quiet duties of a citizen’s life, and can imagine the solicitude those you are expecting to meet have felt for you these terrible years of civil strife, and sometimes think they have shared as much the burden of the war as if they had borne the dangers of the field. Who can tell the number of sleepless nights of a patient wife, the anxiety none but a mother’s heart has known, or of the prayer offered by an affectionate sister.

Soldiers, you are to return to all these. The blessings so long deferred have come, and as I write in the fast waning hours of the old year, my thoughts turn from my own friends and kindred to those with whom I have been so long associated, and whose patient endurance of suffering has taught me many lessons.

As I look back upon the past four years, they seem like a fearful dream, from which we must awake and find all returned to us as before; but, alas, the mourning garb, the crowded cemeteries, the maimed forms of our heroes, assure us only too well that it is a fearful reality. As a nation, how can we repay you for all you have done for us. I feel that I owe you much, and trust I shall ever remember the debt of gratitude I owe each one of you.

As I have looked upon those lying on their couches, suffering from sickness, terrible wounds and mutilated limbs, cheerfully, bearing it all bravely, enduring agonies untold, and even in their dying moments expressing their devotion to the ever glorious stars and stripes; and as I read of the cruelties inflicted upon our prisoners in Richmond, Andersonville, and other places, I could not but feel a sort of reverence for the man who bore the name of soldier, though sometimes I have felt sorrowful, indeed, when I have seen them in a condition in which they must have forgotten their obligations to their friends and country. But those have been rare instances, comparatively, and I thank you, soldiers, for the kindness and courtesy shown me by your comrades, and now regret that I could not have done more when the opportunity presented, for the brave ones of our Union army, though I thought I did all time and strength would allow. I feel that it is so little when you have done much for us all, helped to sustain the best and noblest Government the world ever saw, and which shall last for ages as a witness of your courage and fidelity, blessing the whole world by the example of the sustaining power of a State founded upon the principle of Republicanism.

Through danger, privation and sickness you have proved your loyalty to the flag of the free. As I contrasted in my mind the difference in the state of the country now and a year ago, I could but think we have cause of gratitude to that Great Being who has mercifully and wonderfully preserved us a nation. And when our beloved President was rudely stricken down by the assassin’s hand, how calmly the ship of state moved on with a new pilot at the helm.

We cannot forget those whose lives have been offered up on the altar of liberty. May their memory ever be sacred to us, and by our interest and care for the orphan and widow of the soldier, prove that we are not unmindful of their claims upon us.

A grateful nation will ever point with pride to the hundred battle fields gory with her patriots’ blood, and exultingly ask other nations to vie with her in instances of dauntless courage and unflinching heroism. Belmont, Donaldson [Donelson], Shiloh, Wilderness, Gettysburg, and hundreds of others, will pass down to generations yet unknown; and as they reap the blessings of those victories, they will look back with a patriotic pride to their ancestors who so nobly came forward to uphold the Government of the United States in her time of peril.

I beg your pardon for thus long trespassing upon your time, but as this will be the last New Year we will meet in these relations to each other, I could not forbear saying these few words to you, trusting that you will each bear with you in all the future battles of your lives the kind remembrance of one whom you met in your soldier life.

May all the blessings of Peace and Christian faith be your portion.

[1] Maybe it goes without saying but I will say it anyway: I avoided the quotations of soldiers’ recollections of resulting drunken mischief and the like.

———————————————————————————————————————

Promoting the book (part 1) (added 20 May 2022)

Since your book came out a few years ago, do you still do book promotions (besides on the website)?

Yes – now and again, I am asked or given an opportunity to pitch my book. In the past, I have done a number of in-person promotions at museums, history conferences, and Civil War Round Table groups, to name a few. (I was even invited to read a few Illinois soldiers’ quotations from their letters about experiences with liquor, when I was at a brewery’s rollout event for a new beer.) I have a mental list of “elevator speeches” and talking points that I usually can expound upon at a moment’s notice.[1] Some of these are on other pages of this website.

In addition, whenever I have a Civil War-related article published, usually there is a sentence or two about the writer. Those often start like this: “Mark Flotow is the author [or editor] of In Their Letters, in Their Words . . .” I also have business cards with an image of the book’s cover on one side. (They also serve as reasonable bookmarks.) I have given away at least 500 of those in the past two years.

Whenever I get the opportunity, I enjoy hearing (or reading) readers’ reactions and thoughts about the book. I definitely am sometimes surprised by them, probably because I have such an ingrained perspective as the author/editor. In any case, readers’ feedback has broadened, and sometimes deepened, my insights about Illinois soldiers and sailors during the Civil War era.

Earlier this month, I was asked by Southern Illinois University Press to do a brief podcast “spot” for their “Inside the Blanket Fort” as part of Blanket Fort Radio Theater. You can find this series of BFRT podcasts here: https://news.wsiu.org/podcast/inside-the-blanket-fort It likely will be posted on a Thursday later this month. The roughly three-minute script follows.

*****

In Their Letters, in Their Words: Illinois Civil War Soldiers Write Home is a themed social history book and was written, essentially, by the soldiers themselves.

How did this book come about?

In 2013, I was looking for a book like this one, but I was unsuccessful. At the time, I was writing poems to commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War. So, instead, I decided to scour Illinois soldiers’ personal letters to understand the mindsets, speech, and everyday life of those who had lived (and shaped) the war era. I wanted to know what was important in their world and how they might express their thoughts to others. Part of what came through was how soldiering during the war affected their perceptions and opinions.

I started from scratch and simply read soldiers’ original letters at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. I gradually mastered reading and transcribing scrawled cursive writing in ink (and sometimes pencil) on 150-year-old paper. Those heartfelt letters, originally sent to family, friends and sweethearts, became my portals into their private thoughts and lives.

I was fascinated by what I found, and I began sharing my readings with a select group of friends and colleagues, who mostly were neither historians nor those who had an interest in the Civil War era. I ended up writing forty-six essays, one each week, and sharing them with my far-flung group through email. They also became fascinated. And let’s face it – there is a certain allure to reading other people’s mail. Those essays became the seeds of the current volume. Thus, I wrote the book I originally had sought in 2013.

The book features 165 Illinois soldiers and over 500 topically-arranged quotations from their combined letters. Chapter titles include: A Lifeline of Letters; Managing Affairs from Afar; Seeing the Elephant; and Southern Culture through Northern Eyes. Since the readers gain an intimate knowledge of the individual letter-writers, it concludes with a brief biography for each soldier appearing in the book.

In the end and at its essence, it is about all soldiers, in all wars. The book’s dedication reads: “To Illinois’s soldiers and sailors, past and present.”

Here is a brief extract.

[written from a] camp near Vicksburg, Mississippi, July 24, 1863, to wife, Hattie

During the last two days we got nothing to eat except a little coffee & a very small allowance of hard bread so of course when we arrived here everybody was tired & hungry & cross yet when I found two letters from you awaiting me I forgot all & was soon never in a better humor in my life. . . . Certainly no tired hungry footsore man felt sooner at ease with mankind generally & was sooner fast asleep than I & let me assure you that at such a time no one appreciates the fact that he is “remembered at home” more fully than the soldier

—2nd Lieutenant Z. Payson Shumway, 14th [Illinois] Infantry [regiment], [from] Christian County

One does not have to be a Civil War aficionado to feel the appeal of the book. Nevertheless, I was honored and humbled that it was recognized by the Illinois State Historical Society with the Russell P. Strange Memorial Book of the Year award for 2020. I hope you will have the opportunity to enjoy the book as well.

*****

[1] An “elevator speech” is a business pitch that fits into the time it takes for a typical elevator ride.

———————————————————————————————————————

Unmarked Civil War graves (added 13 May 2022)

With Memorial Day being a few weeks away, do you know how many Civil War soldiers are buried in unmarked graves?

Many Civil War soldiers, still, lie in unmarked graves or at unidentified locations. Of course, their collective magnitude is an unknowable number.

“Pensive on Her Dead Gazing”[1]

Pensive on her dead gazing I heard the Mother of All,

Desperate on the torn bodies, on the forms covering the battle-field gazing,

(As the last gun ceased, but the scent of the powder-smoke linger’d,)

As she call’d to her earth with mournful voice while she stalk’d,

Absorb them well O my earth, she cried, I charge you lose not my sons, lose not an atom,

And you streams absorb them well, taking their dear blood,

And you local spots, and you airs that swim above lightly impalpable,

And all you essences of soil and growth, and you my rivers’ depths,

And you mountain sides, and the woods, where my dear children’s blood trickling redden’d,

And you trees down in your roots to bequeath to all future trees,

My dead absorb or South or North – my young men’s bodies absorb, and their precious precious blood,

Which holding in trust for me faithfully back again give me many a year hence,

In unseen essence and odor of surface and grass, centuries hence,

In blowing airs from the fields back again give me my darlings, give my immortal heroes,

Exhale me them centuries hence, breathe me their breath, let not an atom be lost,

O years and graves! O air and soil! O my dead, an aroma sweet!

Exhale them perennial sweet death, years, centuries hence.

*****

Through the lens of Walt Whitman’s poem, it is a number of dead, and their locations, only “the Mother of All” – or, God – knows. “O years and graves” – where are they all now?

At the Battle of Arkansas Post (9-11 January 1863), a former Illinois soldier recalled the burying of the dead.

from “My Civil War Memoirs and Other Reminiscences” (1935)

we gathered up the wounded for both sides and put them on hospital boats to send them to hospitals to be cared for by the doctors and surgeons. Many of them had to have their legs or arms cut off, or their bodies probed to find lodged bullets, such is the horrors of war, next we gathered up the dead of both sides. placing them in different places according to which side they belonged to. The Rebels we buried with their heads next to the Rebel Fort and their feet to the south toward the arkansas river, we dug a long trench about six feet wide and three or four feet deep laid them in, and covered them up with dirt, our men we took out about a mile in the woods northwest of the Rebel Fort, we dug a seperate grave for each one, placed the bodies in the graves and spread a rubber blanket over them and filled the graves up with dirt.

—former Sergeant William R. Eddington, 97th Infantry, Macoupin County

During the Civil War, it was common for the victors to see to the wounded and the dead. (Sometimes, both sides participated in caring for their own wounded and burying their own dead, under a flag of truce after a battle.) Often, the enemy’s dead were buried in trenches or other mass graves, without identification, to expedite the process as much as possible.

Graysville, Georgia, March 22, 1864, to wife, Grace

last Sunday myself and several officers of the regiment took a ride over [the] battle field of Chic[k]amauga we went over the whole field and of course we took a special interest in the parts where our regiment fought the trees in some places are Cut down so much by the artilery that it looks as if a tornado had swept over the field, all the trees and stumps are pluged all over with bullits it is astonishing to think that any one could have come of[f] safe without being hit, at the place where we made the last stand the ground is Covered with Cartridge papers which in itself shows how desperate the struggle must have been, all the buildings that were on the field had been burnt down by the exploding shells every thing looked desolate, every hundred yards you would come upon a little graveyard where the rebels had been buried with head boards giving the name of the men regiment &c. our own men were Covered over where they fell they had dug a ditch about six in[“ch”? – damaged, missing paper]es deep on each side of the body throwing the earth over it, that was all they did for any [of] our men that most of the bodies they left without burial, our own troops had to do it after the Battle of Missionary Ridge, when we again got possession of the Battle field of Chic[k]amauga,

—Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Raffen, 19th Infantry, Cook County

Another Illinois soldier distinctly remembered the post-battle mass-interment process, well over a year after its occurrence.

Corinth, Mississippi, August 7, 1863, to sister

At the battle field of Shiloah [Shiloh, Tennessee] they took big government waggons, and hauled the dead men together, the same as you would haul hay up north, the wagons would hold about 25 or 30 men, and they would put from 6 to 8 loads in a place It took a week to get them all burried.

—Private Almon Hallock, 15th Cavalry, LaSalle County

It is no wonder there are likely many tens of thousands of unmarked graves from the Civil War. In addition, there were instances, like after the Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia, where unlocated dead soldiers were not buried at all. Of course, not all soldiers who died in combat were upon large-scale battlefields.

camp south of Nashville, Tennessee, November 8, 1862, to wife, Julia, and children

yesterday morning a band of forty or fifty [guerrillas] came darting into the road from among the hills to take or destroy what they supposed to be the rear train of our army but it happened to be the train of the division in advance of us and our advance pounced [on] them quicker than lightning killing seven and wounding several more. we just passed on and left them laying on the road side dead for some one that might chance that way to throw some dirt on Just enough to keep them from stinking us as we pass for they are not worthy a decent burial.

—1st Lieutenant Philip Welshimer, 21st Infantry, Cumberland County

In some locations, where soldiers had been buried in farmers’ fields, their mortal remains were plowed (up, under, or otherwise scattered) in subsequent years. And I would be remiss regarding this broader topic if I did not mention the many soldiers who did have marked graves yet were never associated with the Civil War, either as someone who died during the war or survived as a veteran. Currently, there also are the numerous markers and monuments to the “unknown soldier(s)” from the Civil War, which are fitting reminders in their own way.

Prior to the Civil War, it was the duty of the Quartermaster General’s office to see to soldiers’ burials. The volume of the Union Civil War dead resulting in officially amending that responsibility to the commanding officers. There were no “dog tags” or other required individual-soldier identifications carried at all times. Suffice it to say, there were many instances where individuals were not identified at the time of burial, especially after battles.

Given all of the above, how can we now honor the Civil War dead, especially those whom remain unknown or unlocated, besides through decorating their resting places with flowers or otherwise commemorating their sacrifices, on Memorial Day?

As a direct consequence of the war’s dead, the Lincoln administration created the first national cemeteries. By the end of the war, three of those were in Illinois: Camp Butler, Rock Island, and Mound City (on the Ohio River). Post-war, there soon were efforts by the U.S. Government to better organize and create more cemeteries dedicated to Union soldiers. Additional national cemeteries were often near former battlefields or hospitals. National efforts to recognize the Confederate dead did not occur in earnest until the twentieth century. Initially, those energies were focused on Confederates who had died while in Union hands, such as at prisoners’ camps and hospitals. Prior to that, private, southern-based organizations were formed for reburying and organizing the Confederate dead.

Whether reburied in 1865 or 1905, it was often wellnigh impossible to provide a name for many soldiers. One estimate I saw suggested that at least half of those reburied were never identified.

Currently, there are about 160 national cemeteries (NC), with the vast majority of those under the authority of the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs. The Department of the Army has two national cemeteries: Arlington NC, and the Soldiers’ Home NC in Washington DC. The National Park Service oversees fourteen national cemeteries.

In Illinois, there are nine national cemeteries which, I believe, have at least some graves of Civil War soldiers.[2] Those are: Alton NC (established 1948), Camp Butler NC (1862), Confederate Mound at Oak Woods Cemetery (Chicago, 1903?), Danville NC (1898), Mound City NC (1864), North Alton Confederate Cemetery (1867), Quincy NC (1868), Rock Island Confederate Cemetery (1863), and Rock Island NC (1863). And of course, there are Illinois Civil War soldiers’ gravesites at other cemeteries throughout Illinois, as well as those buried in cemeteries in other states, including states established long after the Civil War ended.

In terms of honoring the Civil War dead and how the massive numbers of soldiers’ deaths impacted their memorialization by family members and others, I recommend Drew Gilpin Faust’s book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008). In particular, relative to the topic of this posting, I suggest reading chapter 7, “Accounting: Our Obligations to the Dead” (pages 211-249).

Finally, although Whitman’s poem was originally written before there were national recognitions of what became to be known as Decoration Day, to honor soldiers – South and North – by “decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion,”[3] I would suggest “Pensive on Her Dead Gazing” is a fitting soldier tribute for Decoration Day (Memorial Day). “Lose not my sons” is part of Whitman’s cry for remembrance “centuries hence.” The many battlegrounds where soldiers’ “precious precious blood” was lost are thus consecrated earth, streams, trees, airs, and mountainsides, whether they be with or without marked graves. While I truly respect and honor all soldiers in their graves on Memorial Day, I think Whitman’s poem is an appropriate way to remember and cherish all those Civil War soldiers who lie without graves or without recognition, wherever they might rest across our nation.

[1] Walt Whitman, Civil War Poetry and Prose, Dover Thrift Edition, republication from selections of Drum-Taps (1865), Sequel to Drum Taps (1866), and Leaves of Grass (1891–92), (New York: Dover Publications, 1995), 38. Whitman wrote “Pensive on Her Dead Gazing” in 1865.

[2] Or, they contain at least Civil War veterans.

[3] Robert B. Beath, History of the Grand Army of the Republic (New York: Bryan, Taylor & Co., 1889), 90. Note that a day dedicated to the decoration of Civil War soldiers’ graves did not originate with the GAR, but this Union fraternal organization built on that idea by suggesting, in 1868, that May 30th of each year be dedicated to that pursuit.

———————————————————————————————————————

Camp Butler named after whom? (added 6 May 2022)

In other postings you have stated that Camp Butler, near Springfield, was named after William Butler. Is it possible the camp was named after General Benjamin Butler, who was well-known during the Civil War, including in 1861?

I have entertained this question, albeit in person, on a few past occasions. I think it is worth stating a few words about both Major General Benjamin Butler and Illinois Treasurer William Butler during the Civil War.

Already by May 1861, President Lincoln had appointed Benjamin F. Butler as a major general within the volunteer army. (Prior to the war, Butler was a Massachusetts lawyer and a pro-southern Democrat.) While sympathetic to Southern states’ rights, he viewed secession as treason and sided with the Union even before war hostilities ensued. He also had been active in the leadership of the Massachusetts militia prior to the Civil War. In May 1861, he and his new army recruits successfully occupied secessionist-leaning Baltimore, which in turn helped to secure nearby Washington DC. His early exploits earned him his major generalship, as well as some fame in the national press.

Later in May, he was ordered to take possession of Fort Monroe, at the southern tip of the Virginia peninsula as well as the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. He was able to do so and quickly expanded Fort Monroe’s defenses. Despite subsequent military blunders by Butler near the fort in Virginia that June, Fort Monroe remained in Union hands for the rest of the Civil War. In addition, during his time at Fort Monroe, he independently decided that slaves who came into the Union lines from Viriginia were not subject to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and instead considered the slaves as contraband of war. In a way, he was ahead of the Lincoln administration regarding the status of Southern slaves relative to the war. Some of Butler’s contraband thinking was incorporated into the First Confiscation Act of 1861, which became law in August.

Also in August, Butler-led army and naval forces captured Confederate forts Hatteras and Clark on the coast of North Carolina. The popularity of those victories, which were not long after the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, led to the Lincoln administration having Butler spearhead soldier recruitment efforts in his home state of Massachusetts shortly thereafter.

Since Camp Butler, near Springfield (IL), was so-named by early August 1861, I will end my brief biography of Benjamin Butler at this point. Much of the above did garner B. Butler a certain amount of national notoriety, such that many people in Illinois knew who he was relative to the Union’s war efforts. (Parenthetically, I should add that by the end of the war, B. Butler would be well-known for both his military and war-related administrative missteps. Despite his pre-war state militia involvement, his lack of military skills was evident during the Civil War on a number of occasions.)

William Butler (1797-1876) was an Illinois Treasurer (1859-1862) and longtime Sangamon County resident. He also served as the Sangamon County Clerk to the Circuit Court from 1836 to 1841. W. Butler was also a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. Butler had assumed some of Lincoln’s debts when Lincoln was a new representative in the Illinois legislature and, for a few years, Lincoln took his meals with the Butlers in Springfield, starting in 1837.[1] In addition, Butler had been active in getting Lincoln nominated for president at the Republican National Convention in Chicago in 1860.[2]

In April 1861, Illinois Governor Yates sent W. Butler with a letter to President Lincoln expressing Illinois’s support for raising troops for the Union armies. It read, in part:

Our people burn with patriotism and all parties show the same alacrity to stand by the Government and the laws of the country. Illinois is a unit, and will be true to her former reputation for courage and patriotism.

Please answer by messenger, Mr. Butler.[3]

Thus, W. Butler was directly part of the Governor Yates administration’s efforts to raise and organize recruits for the federal war efforts.

However, there is also indirect evidence that W. Butler had connections that may have led to the military post being named in his honor. While there appears to be no existing Illinois government or U.S. military records relating to how and why the initial site of Camp Butler was selected (at Clear Lake, about six miles northeast of Springfield), Butler would have been well-qualified to suggest potential sites for a large recruitment and training camp. In addition, Butler had briefly owned the Clear Lake property. He had bought it at public auction for $10 in May 1847 and sold it privately to Strother G. Jones for $100 in April 1848.[4] So, Butler, having moved to Sangamon County in 1828, was well-connected to people throughout the area and, having been a County Clerk, knew the local lands and properties.

In short, there is no reasonable doubt that Camp Butler in Sangamon County was named after the then-current Illinois State Treasurer, William Butler, as was stated in a Springfield newspaper.

“Camp Butler.”

The camp at Clear Lake is to be named Camp Butler, in honor of our worthy State Treasurer. Gov. Yates and the Adjt. General are busily engaged in arranging for the formation of the regiments, and the accepted companies with their regimental organization, will probably be published tomorrow. Col. Hick’s independent regiment, of Marion county, is to arrive on Tuesday. The independent regiments already formed will all be in camp before the close of next week. The regiment of cavalry, hithertofore ordered to rendezvous at Bloomington, is to go into Camp Butler.

—Illinois Daily State Journal, August 2, 1861.

[1] Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life. 2 vols (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 1:130.

[2] Butler was one of several Illinoisians who assisted Judge David Davis at the Chicago Convention; Burlingame, A Life, 1:602.

[3] Letter from Richard Yates (and additionally signed by Lyman Trumbull, Gustavus Koerner, William Butler, Jesse K. DuBois, and O. M. Hatch) to President Lincoln, April 17, 1861, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), ser. 3, vol. 1, 80-81. Since W. Butler was a friend of Lincoln, Butler was sent in person to the White House to deliver the letter and meet with the president.

[4]Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds Office, Deed Record Book Z (p. 443) and AA (p. 467), Genealogical Society of Utah, microfilm, 1981, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C95K-S9L7-R?i=176&cat=330737 and https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C95K-S92Q-J?i=490&cat=330737

———————————————————————————————————————

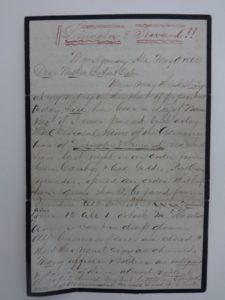

Early Camp Butler letters (added 29 April 2022)

Regarding the two major training camps in Illinois – Camp Butler and Camp Douglas – Butler, near Springfield, was established first. What did the earliest letters written from Camp Butler say about soldiers’ lives there?

The Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Museum in Springfield, Illinois, has two of the earliest Camp Butler letters I have come across.[1] Both were written within the first month of the camp’s operation. (Camp Butler first opened on 2 August 1861.)

Here is the first of the two letters. (My thanks to Chuck Hill of the GAR Memorial Museum for access to his transcriptions of these two letters.)[2]

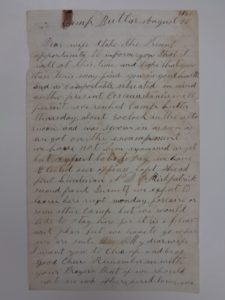

[Letter image courtesy of the GAR Memorial Museum Archives, Springfield, Illinois.]

Camp Butler, near Springfield, Illinois, August 30, 1861, to wife, Harriet

Dear wife I take the Present opportunity to inform you that I [am] well at this time and hope that these lines may find you in good health and as comfortable situated in mind as the present circumstances will permit. we reached Camp butler Thursday [29 August] about 3 o’clock in the afternoon and was sworn in as soon as we got on the encampment we have not been examined as yet but expect to be to Day we have Elected our officers Capt Shead [Shedd] first Lieutenant N B [Nathaniel R.] Kirkpatrick [and] second [Lieutenant] frank [Francis G.] Burnett we expect to leave here next monday for cairo or some other camp but we would like to stay here for it is a pleasant place but we have to go where we are sent. My dear wife I want you to Cheer up and be of good Cheer. Remember me with your Prayers that if we should not see each other here below we

[p.02]

[in] this world we may meet where we shall not be disturbed by war. we had a pleasant trip we left judge Hoagland son on the road at Avon between Galesburg an[d] Macomb in MeDonna [McDonough] Co. Ills there was another left at Camp point we have 99 men in [the] company at this time as we are not likely to stay here you need not write till you receive another letter I will close at this time my love to the friends

I remain your affectionate

Companion till Death

R R Crist

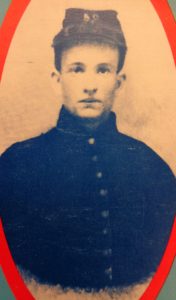

—Private Robert R. Crist, Company A, 30th Infantry, Mercer County

According to the 30th Illinois Infantry’s regimental history, it was organized at Camp Butler August 28, 1861, with Colonel P. B. Fouke, commanding.[3]

Robert Russell Crist (born 4 June 1820, in Ohio), a blacksmith from Aledo, in Mercer County, was 41 years of age when he joined the 30th Illinois Infantry Regiment. Crist had married Harriet Wood (22 April 1847) in Ohio; they had no children.[4] He was mustered into the infantry the day he arrived at Camp Butler (29 August 1862), but wrote “we expect to leave here next Monday for Cairo or some other camp.” It turned out his future traveling information was good, as he and much of the rest of the regiment apparently left for Cairo perhaps on that Sunday (1 September). That meant the regiment was going to be trained at or around Cairo instead of at Camp Butler. Some other regiments were also at Camp Butler during his brief stay. For example, on 31 August, there were 3,910 soldiers reported as present at Camp Butler.[5]

At about this time, two Springfield newspapers reported on activities at the camp.

“Camp Jottings.” Camp Butler, Thursday Evening.

Friend local:–There is scarcely anything of interest to speak of as having occurred in camp today. In the forenoon Col. Reardon’s regiment left for Carbondale. In the afternoon, the following companies arrived: From Mascoutah, St. Clair county, Samuel Shimminger, captain, from Logan, Edgar county, Captain Jason B. Sprague; from Mercer county, (98 men,) Capt. Shedd. Besides these I understand that some companies are expected in the evening, but as I have no time to wait for them you must call at the adjutant general’s office and ascertain their names and number. . . .

The scenery at the camp wears the same appearance still. Drilling, marching and counter-marching, at appointed intervals, go on, and the tramp of uninstructed soldiery makes its noise as I write. There is a refreshing breeze throwing the smooth waters of the lake into ripples. The soldiers, such of them as have been able to procure a pass, are luxuriating in the comfort of a bath, the noise of the fife and drum is echoed through the trees from the far off extremities of the camp to its picturesque surroundings. In a word the encampment looks the personification of animated, jovial life.

—Illinois Daily State Register, August 30, 1861. [bolding added]

“Arrived Yesterday.”

Capt. Davidson’s company, from Macoupin county; Capt. Jason R. Sprague’s, from Edgar; Capt. Warren Shodd’s [Shedd’s], from Mercer, and four companies of Col. Hovey’s Regiment, arrived in camp yesterday.

—Illinois Daily State Journal, August 30, 1861. [bolding added]

Both of these articles confirm parts of what Private Crist wrote in his letter, as well as that Camp Butler was a busy place. Besides the comings and goings of the various companies and regiments, the Register article gives a sense of some of the camp’s usual activities, such as drilling and the sounds of “the fife and drum.” One might question if Camp Butler was “the personification of . . . jovial life” but, if nothing else, the novelty of it all likely was still part of the soldiery’s sensations, at the time. Private Crist also seemed favorably impressed and stated: “we would like to stay here for it is a pleasant place.” Soldiers could bathe in nearby Clear Lake, and the weather was agreeable regarding the tented living quarters at early Camp Butler.[6]

“Camp Jottings.” Camp Butler, Friday Evening.

The camp presents no new feature today. Everybody seems to be pursuing the even tenor of his way. The machinery of the camp progresses, and in all its details would seem to be perfect. We have had no arrivals since my last, nor yet any departures. I understand that the following companies, belonging to Colonel P. B. Fouke’s regiment, have received marching orders, to leave for Cairo on Sunday, to join Gen. McClernand’s brigade: Capt. Thomas G. Marckley’s company, Capt. I. P. Davis’ company, Capt. Harlan’s company, Capt. Rhodes’ company, Capt. Shedd’s company, Capt. James R. Wilson’s company, Capt. Thomas McClurken’s company.

—Illinois Daily State Register, August 31, 1861. [bolding added]