Questions & Answers for postings October 2019 through December 2020

Each week, I will choose a question or comment from readers about Illinois Civil War soldiers. I will do my best, each Friday, to respond to a selected question. I would prefer to answer inquiries directly related to the book or Illinois Civil War soldiers, but I will at least read and consider all reader submissions. Please see the sidebar (at the bottom) on how to submit a question for this page. =====>

———————————————————————————————————————

———————————————————————————————————————

Christmas descriptions (added 24 December 2020)

Did Illinois soldiers in the field celebrate Christmas?

Yes, they did, to various extents, when possible. Generally, there were no Christmas truces, per se, and there were some military actions by Civil War armies close to 25 December. An inspection of E. B. Long’s The Civil War Day by Day shows that there was some Christmas Day skirmishing (1861); General Sherman maneuvering his army north of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prior to the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou (29 December 1862) and armies getting in place prior to the Battle of Stones River near Murfreesboro, Tennessee (which started 31 December); some skirmishing on Christmas and minor naval actions in the eastern theaters of war in 1863; and on that same calendar day in 1864, Federal troops were repulsed in trying to take Fort Fisher, North Carolina, and there was skirmishing related to the pursuit of the remnants of Confederate general Hood’s army in southern Tennessee after the Battle of Nashville (15-16 December).[1]

Here is a detailed Christmas Day, 1862, description of camp antics during some hours of relaxed military discipline. [Editor’s note: the following is a literal transcription and contains offensive, derogatory words.]

camp near Gallatin, Tennessee, December 25, 1862, to parents

this is Christmas evening but there is very little appearance of any frolicks and “nary Gall” this has been spent as a kind of holy day in the Regt in the morning the camp Gaurd was called in, and the men got privliege to go any where within five hundred yards of camp. in the fore part of the day the boys played ball [i.e., baseball] and cut up [e.g., frolicked, joked] in a general way. W. Frasier W. J Hill & I went to try and buy some turkey or chicken but failed in that so we just came back and tryed it the old way on crackers & pork with a few beans &etc. after dinner the old drum beat at head quarters and we all repaired thither. we looked for battalion drill or some other thing of this kind but judge of our surprise when, instead of that there stood a big box bottom up and on it a little “niggir” dancing and another old one fiddling like fun. after he got through dancing then came a regular stampede and shoulder straps [i.e., being an officer] woudnt save a man a bit they would catch a capt or Leut and set him on the box and there was no escape he either had to dance or stand his time out any how. we got the Ajutant up and here he stood for a good while and then we let him down next on the programe, here they come with the Leut Col. and set him up on the box he lost his left shoulder strap in the scuffle. he stood and laughed for a little while and then jumped down and said he could get a substitute and catched the nigger and set him up again this caused a general cheering and the crowd broke up after an hours fun – it is now four oclock and still there is no sign of the boys stoping playing ball and everything that will amuse in the slightest

[But it was still war times, and his letter continues . . .]

I am sorry here to state that on tuesday [23 December] we followed one of our most estimable members of the Companie to the grave as mourners the mu[si]cians went to the front with their drums muffled. then eight men with their guns brightened. then came the whole Company moving in slow procession. at the grave the chaplain Preached a short sermon and prayed we then marched to camp on a quick march and in the Companie he appears to be entirely forgot already

[and he also mentioned political rumors . . .]

the papers here state that Lincolns whole Cabinet has resigned. is this the case. if so what do you think about it.?

—Corporal James Crawford, 80th Infantry, Randolph County

Although Gallatin, Tennessee, is directly north of the forthcoming battle at Murfreesboro, instead on 26 December the 80th Illinois Infantry Regiment moved further north, into Kentucky, in pursuit of Confederate general John Morgan’s forces.

Somewhat in contrast, here are excerpts from a private’s two letters as Christmas 1864 approached.

Nashville, Tennessee, December 21, 1864, to sister

I hope you will have a merry Christmas up in Ill, this winter I should be glad to be at home this Christmas and partake of the goodies. but I am not going to cry about it

Nashville, Tennessee, December 23, 1864, to “Mother and Children”

My health is tolerably good at present, with the exception of my limbs & joints which frequently feel stiff & painful this season of the year, and which is doubtless the effect of long & severe exposure while in the service. . . . I hope you are all well and in a good humor. and trust you will have had a happy Christmas, and enjoyed yourselves as gaily and cheerfully as snow-birds. and to some benefit & improvement to you all, as well as to the great satisfaction to and approbation of Mother.

—Private William Dillon, 40th Infantry, Marion County

It seems Private Dillon was somewhat melancholy about missing the holiday festivities at home with his family.

Even more in contrast, in 1863 the following soldier actually was ruing how Christmas was sometimes celebrated in the army.

Big Black River, Mississippi, December 27, 1863, to brother

Our Colonel is not in command yet but will probialy get the command in a few days He proves to be a very good officer and almost worships the Regiment the only trouble is he tries to make them do every thing that any other Regiment ever done to show off Our Gens. gave orders to ishue three rations of whiskey to the Soldiers on Christmas day The soldiers and officers wer most all drunk and nothing but fights and rows all day and night I wish they would dismiss our Gens. for ishuing such orders I never wanto see an other Christmas while I am in the army if they let the soldiers have whiskey In our Regiment they got up a Temperance plege and over two hundred si[g]ned it

—Private Cyrus Randall, 124th Infantry, Kane County

Finally, here is a fourth soldier, a chaplain, reflecting on missing the 1863 Christmas at home, and missing his wife in particular.

Whiteside, Tennessee [near the Georgia border], January 6, 1864, to wife, Anna

You want to have me say that I am your husband Well so I say then but I would much rather prove it by —- you know what . . . Capt [Frederick] Garternicht [of Co. G] has just heard that a little girl made her appearance at his house Christmas night quite a Christmas present he thinks. How do you suppose the thing happened? I dont know of course but he went home on leave of absence last March [i.e., nine months prior . . .] & he told me some time ago that when he was home he “played dunder” you can guess what that means.

—Chaplain Hiram Roberts, 84th Infantry, Adams County

One might well guess that “you know what” and “played dunder” meant something conjugal.

[1] E. B. Long (with Barbara Long), The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac 1861-1865, reprint (New York: Da Capo Press, 1971), 151, 300-302, 449, 611, 615.

———————————————————————————————————————

Phonetic spelling (added 18 December 2020)

There are several phonetic spellers among the soldiers in your book. Does this mean the phonetic spellers were at least somewhat illiterate?

Fundamentally, literacy is a progression of understanding written language rules and exceptions. Spelling is a part of literacy skills. In that light, literacy is a continuum on which individuals fall and, somewhere, there is a fuzzy, arbitrary line where those below could be considered illiterate. In short, literacy is more than being able to sign one’s name.

Regarding spelling skills, “We can use ‘phonetic spelling’ for most words because there’s a direct correspondence between the sounds and the written letters. About 84 percent of English words follow the sound-spelling rules of the language.”[1]

Children generally go through a “phonetic stage” in learning correct spelling.

“The correct speller fundamentally understands how to deal with such things as prefixes and suffixes, silent consonants, alternative spellings, and irregular spellings. A large number of learned words are accumulated, and the speller recognizes incorrect forms. . . . the major need for inventive spellers who are beginning to read is to have someone to answer their questions and correct their mistakes, such as the misreading of words, when necessary.”[2]

I sometimes use voice-recognition software as part of a speak-to-type process. It is amazingly good at converting speech to written words, but it also is often tripped up by homonyms (e.g., corps vs. core, wait vs. weight, to vs. too vs. two), possessive cases (e.g., the bayonet’s gleam vs. the bayonets gleam), and irregular spellings (e.g., some proper names). The software does “learn” a user’s spelling preferences (say, for often used names), but generally humans learn better when, as mentioned above, they can get answers to their spelling questions and have help with correcting their mistakes. Soldiers, as adults, may have sometimes had a stigma about asking fellow soldiers for help with their literacy skills and thus became “stuck” in the phonetic spelling stage. In any case, there was a range of literacy skills evident in Civil War soldiers’ letters.

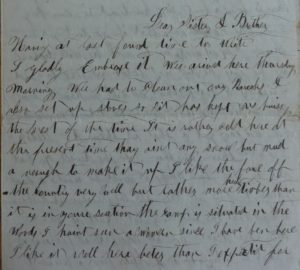

All that stated, I would suggest Civil War phonetic spellers are sometimes easier to “hear” as to what their voices and manners of speaking were like through their personal letters. Some examples of this come from letters written by Sergeant Ashley Alexander of Winnebago County. Here is an image of a letter he wrote while at Camp Butler, Illinois, dated 3 March 1862.

His penmanship is about average among the Illinois Civil War soldiery, and he is somewhat a phonetic speller. In the following transcription of a later letter, I have used brackets – [ ] – to indicate misspelled words. (Note that like in many such soldiers’ letters, punctuation was lean or almost nonexistent, irrespective of the soldier’s spelling ability.)

Clear Spring, Maryland, September 20, 1862, to “Frien[d] Akerley & family”

With pleasure I sit down to Inform you that I am still a live [alive] and well & I hope that these few lines will find you all injoying [enjoying] the same blessing I should have a riten [written] before but wee [we] have benn [been] mooving [moving] a round [around] all the time I spoase [suppose] that you with out [without] doubt have heard of our leaving Martinesburgh [Martinsburg] and going to harpers ferry the Rebils [Rebels] drove us from thare [there] and when they got to the ferry Wee [we] got into a tighter plais [place] still wee [we] got thare [there] three weeks a go [ago] last friday and on Saturday they comenst [commenced] fiting [fighting] they fought all day and most all knight [night] and Sunday they plantid [planted] their Batteries on london hights [Loudoun Heights] and they shelled us Rather earley [early] I thought they had over 40 pieses [pieces] on them hights [heights] and as nise [nice] a rainge [range] as you ever saw an [and] you can only imagin [imagine] It to bee [be] a rather of a warm time they had uss [us] all suroundid [surrounded] If you had this pen I dont [don’t] think that you would blaim [blame] me If I did not right [write] for It is the poorest damd [damned] thing I eversaw [ever saw] so you cant [can’t] expect mee [me] to rite [write] mutch [much] Wall [Well] they spiked them largest gunes [guns] a bout [about] 1 oclock [o’clock] Sunday they was tow [two] of their gunners pict [picked] off so the damd [damned] fool General Milles [Miles] orderd [ordered] them to spike them to make It short I[t] was a poor damd [damned] cowerdly [cowardly] surrender [surrender] and at 8.8.o.clock Sunday knight [night] Generall [General] white [White] says that he was a going to lead this cavalry [cavalry] out of theire [there] up into pensylvania [Pennsylvania] or to hell So wee [we] cut our way out of that plaise [place] without mutch [much] loos [loss] and did not get into anny more [anymore] truble [trouble] till wee [we] got to Sharpes Burgh [Sharpsburg] thare [there] the Rebiles [Rebels] fiered [fired] into uss [us] again wee [we] runn [run] into cornfields and into woods and and all plaises [places] but into a good road Wee [we] got out of that and did not think of anny [any] difficulty [difficulty] till wee [we] run into longstreets [Longstreet’s] train he and Burnside had ben [been] a fiting [fighting] the day before and he was a retreating to harpers fery [Ferry] to reinforse [reinforce] Jackson Wall [Well] after sckedadling [skedaddling] so mutch [much] wee [we] done some good Wee [We] toock [took] 175 Wagons loaded with Amunition [Ammunition] and provisions and 103 prisners [prisoners] and runn [run] them up into Pa. Wee [We] are a waiching [watching] the Rebiles [Rebels’] moovements [movements] know [now or know] they are on the other side of the patomac [Potomac] and wee [we] are on this side Wee [We] see them evry day [everyday] and talk with them some of the time they say that they wons [won] wont [won’t] be but wone [one] more Batle [Battle] and It will be soon Wee [We] expect to have to leave evry day [everyday] they [there] was a Rebil [Rebel] cap captain and 4 others came and gave them selves [themselves] up day before yesterday they say that they cant [can’t] fite [fight] anny [any] longer without something to eat and tow [two] of them said that they had ben [been] Barefooted tow [two] months they [there] was a farmer came from a Martines burgh [Martinsburg] he said that they [there] was 160 thousand thare [there] and to Winchester freem [Freeman? – a man’s name] I gess [guess] I will not wright [write] a gain [again] for I haint [haven’t] no money to pay the postage and cant [can’t] get any so I will have to stop writing I cant [can’t] cary [carry] paper and half of the time I cant [can’t] get any and so It dont [don’t] pay to rite [write] a fellow [fellow] hase [has] to lay on the ground and to rite [write] I cant [can’t] rite [write] worth a cuss any way [anyway] but when I get back I will tell you all the news wee [we] dont [don’t] get anny [any] news here you hear twise [twice] as mutch [much] as wee [we] do a bout [about] what is going on in regard to the Army

—Sergeant Ashley Alexander, 12th Cavalry, Winnebago County

It some cases, his phonetic spelling gives some insights on how he pronounced words, such as frien for “friend,” spoase for suppose, thare for there, anny for any, and haint for haven’t. For example, wall for “well” suggests he may have had a somewhat western drawl (for the country at the time).

When I give in-person or virtual presentations about Illinois Civil War soldiers’ letters, I have audience members read letter excerpts aloud. It is one of the best ways to imagine hearing voices from the past, especially because so many of the soldiers wrote as if talking.

[1] https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/for-educators/teaching-strategies/evidence-based-literacy-strategy-spelling-regular-words

[2] https://www.readingrockets.org/article/invented-spelling-and-spelling-development

———————————————————————————————————————

Shoes and boots in the army (added 11 December 2020)

There is this quotation in your book: “we was stript Barefoot and marched over the mountains and Rock until the suffering of the Poor Boys is beyond any description or imagination” (page 66). How common was soldier barefooted-ness in the Civil War?

“Shoeless Soldier’s Sonnet”[1]

Steppin’ lively next to the dusty roads,

My small part to keep the Blue Bellies vexed,

Where in the Wilderness we might smite next,

Marching in the brigade of Robert Rodes.

Silence be our watchword, signal in codes,

Rifles ready, high officers have checked

Old Jack’s grand ruse to have their right flank wrecked;

We peers through the woods while the cannon loads.

Lies beyond, out of sight, of our front ranks

Them stuffed haversacks, sugar and bacon,

Beef on the hoof, to go into our stews.

O, My Captain points down the road of planks,

Union position, all for the takin’.

I rise up on blood-stained feet without shoes.

*****

“An army marches on its stomach” (said Napoleon, Frederick the Great, and/or Claudius Galen), but shoe leather helped combat the weather whether on the march or standing still during guard or picket duty.

Major General Burnside Washington, D.C.,

Knoxville, Tenn. Oct. 17 1863

I am greatly interested to know how many new troops of all sorts you have raised in Tennessee. Please inform me.

A. LINCOLN

Burnside replied on October 22: “Your dispatch received. We have already over three thousand in the three year service & half armed. About twenty five hundred home guards many more recruits could have been had for the three years’ service but for the want of clothing & camp equipage. . . . We are suffering considerably for want of shoes & clothing . . .”[2]

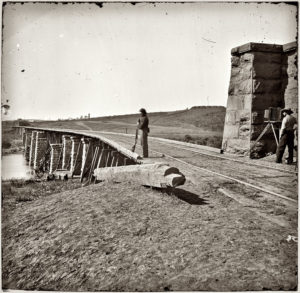

Without a doubt, shoes and boots were valuable commodities to soldiers in both the Union and Confederate armies. Although shoeless-ness is more often associated with Confederate soldiers, look closely at this December 1863 image of a Union soldier guarding a bridge northeast of Knoxville, Tennessee.[3]

Clear Spring, Maryland, September 20, 1862, to “Frien[d] Akerley & family”

Wee are a waiching the Rebiles moovements know [now] they are on the other side of the patomac and wee are on this side Wee see them evry day and talk with them some of the time they say that they wons[?] wont be but wone more Batle and It will be soon Wee expect to have to leave evry day they was a Rebil cap captain and 4 others came and gave them selves up day before yesterday they say that they cant fite anny longer without something to eat and tow of them said that they had ben Barefooted tow months

—Sergeant Ashley Alexander, 12th Cavalry, Winnebago County

After his regiment’s escape from Harpers Ferry, Sergeant Alexander mentioned that among some captured Confederates “tow [two] of them said that they had ben Barefooted tow months.” Granted this was during September, yet marching and maneuvering in bare feet cannot be comfortable.

When I took this picture, below, I praised the Confederate reenactor (in the red shirt) for his realism![4]

camp near Bowling Green, Kentucky, November 1, 1862, to wife, Julia, and children

a wounded [Confederate] Lieutenant told us that he had paid fifty dollars for the boots he had on about as good as a pair I had on I paid five twenty five for in Louisville ky and he sayed shoes was from Eight to ten dollars per pair and nearly one third of Braggs Army was barefooted those that had shoes had stole them on their way up.

—1st Lieutenant Philip Welshimer, 21st Infantry, Cumberland County

Considering what the wounded lieutenant paid (which may have been in Confederate scrip), it is no surprise then regarding the following (which is the full quotation from page 66 of the book).

Benton Barracks, near St. Louis, Missouri, September 9, 1864, to wife, Mattie

I suppose that you have already heard of the misfortune of the 54th Regiment. we was attacted [in Arkansas] on the 24th of August by General [Joseph O.] Shelbys forces. . . . they then made a charge on us and we was over powered and forced to surrender. they rob[b]ed us of every thing we had some of the Boys had nothing left but their Shirt and Pants we was stript Barefoot and marched over the mountains and Rock until the suffering of the Poor Boys is beyond any description or imagination we was put through on the Double Quick for 40 Hours without a bite of any thing to eat

—Private Henry Barrick, 54th Infantry, Douglas County

Private Barrick and comrades were “stript” of items that would have been useful to the victors. Similarly, there is this description of Captain Chauncey Williams’ body found during the aftermath of a battle.

near Peterburg, Virginia, August 19, 1864, to Mrs. Williams

I send you enclosed a lock of hair and one Shoulder strap the only relics of your noble husband, and our brave and honored Captain, who fell on the 16th inst while bravely leading his men on to victory. After the fight I search the field for his body but could not find it. . . . The next day, under a flag of truce we recovered the bodies of our dead. . . . This shoulder strap was all that was left him, his pants and boots had been taken by the rebels, and even the buttons cut off his vest.

—Private William Morley, 39th Infantry, DeWitt County

However, not all Union footwear was worth having.

Nashville, Tennessee, February 10, 1863, to uncle, W. C. Rice

I wish you would get Rapp or some other man to make me a pair of first rate hip boots. . . . I suppose from what I hear they will not cost more than 6,50 there They would bring $13,00 here. The boys are buying grained leather boots of very poor material for 10,00 and 12,00 They do not last 3 months.

—Sergeant James Rice, 10th Infantry, Henderson County

Of course, boots provided more protection than shoes when living outdoors continuously, and in any and all kinds of weather.

Greenville, Missouri, February 22, 1862, to brother

we left Ironton on the 29 of January . . . through the deep snow and snow storm. the first creek we came too was knee deep so all g[ot ?—MSD] their feet wet. the most of the boys wore shoes. about 3 o clock it quit snowing. the wind began to howl through the mountains, and began to frese very fast. then we began to suffer,—wet feet & pants legs frose stiff. at 5 00 we camped. evry man had from 3 to 5 pounds of ice & mud frose to his clothes so we built fires as well as we could and warmed. . . . we covered with our Blankets. it was very cold on that night. next morning there was a good many boys found their feet frost bit and some so badly frosen that they had to be hauled back to Ironton.

—Private George Dodd, 21st Infantry, Edgar County

Finally, it is no surprise that standing out in the rain on guard duty, with wet shoes, could put a soldier in a foul mood.

Paducah, Kentucky, February 1, 1862, to brothers and sisters

While the soldiery who are out in the defense of their comfort happiness & liberties have sacrificed friends, Father & Mother, Brothers & Sisters and in thousands of instances have left Wives & children and all else that pertains to mans happiness in a peaceful life, They (the soldiery) must be the objects of scorn & hisses! and be called rogues and plunderers, while engaged in putting down rebellion & disloyalty, and have come out on the field, the camp, the march, and subjecting our safety our healths our lives to all the dangers attendant to a soldiers life. And now while I write the water is from shoe mouth to half leg deep all around us while on post . . .

—Private William Dillon, 40th Infantry, Marion County

[1] Poem from the Sesquicentennial Civil War Series of poems I wrote circa 2014. This one was inspired by the descriptions of General Jackson’s Confederate soldiers marching on 2 May 1863 in maneuvering to strike General Hooker’s Union right flank at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

[2] Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55), 6:521-2.

[3] This image is from https://pitsnipesgripes.blogspot.com/2013/03/rewind.html

[4] Image taken 1 June 2019 at the Pike County “Lincoln Days” Civil War Battle, Lake Pittsfield, Illinois.

———————————————————————————————————————

Location of first Camp Butler (added 4 December 2020)

On page 23 of your book, you stated that Camp Butler was named after the then-state treasurer, William Butler. Where was the first Camp Butler located?

As I had explained on this webpage (28 August 2020), “the first mention in the Springfield newspapers of what was to become Camp Butler, at its original Clear Lake location, is the following.”

Illinois Troops Accepted.– The thirteen new regiments of infantry recently tendered [by] the War Department, by Gov. Yates, have been accepted. They will be ordered to rendezvous at this city, and will go into camp at Clear Lake, which is admirably calculated to accommodate a large body of troops, affording ample room for drill and evolutions, with plenty of shade and good water. Details will be published in a day or two, and the necessary orders issued.[1]

Here is a mid-August 1861 newspaper article description of the newly established Camp Butler.

At Camp Butler.— We paid a hasty visit yesterday to Camp Butler, and found things looking very lively, and the ground assuming quite a military air. Crowds of visitors are constantly coming and going, notwithstanding the condition of the roads is such that every vehicle leaves behind it a stream of dust like the tail of a comet.

The most conspicuous object in approaching the camp is the sutler’s tent of our friend Myers, who is as busy as a bee the whole time . . .

Alongside his stand are the commissary buildings, from which were issued on Wednesday 1,918 rations, which were probably increased yesterday to 2,500, as several companies arrived during the day. The soldiers occupy themselves as men in camp usually do, and are as fine a looking body of men as any friend of this country could wish. We believe there are about 18 companies of infantry and 11 of cavalry now in camp.[2]

When the weather turned wet, the dusty roads turned into muddy ones, which at times became nearly impassible as a consequence. The above article mentions “commissary buildings” but, otherwise and generally throughout this iteration of Camp Butler, most everyone occupied tents as opposed to wooden structures. The following article emphasizes the canvas nature of the camp environment.

Camp Jottings.

Camp Butler, Friday Evening.

This is been a dreary day in camp. A drizzling, sluggish rain has been falling almost uninterruptedly since noon, and the soldiers, unless those detailed for special duty, are confined to their tents. Drill exercises are for the hence dispensed with, and instead of the tramp and other “pompous circumstances” of camp life, we hear nothing but the coarse jestings of the men as they recline in true soldierly negligence in their canvas tenements. . . .[3]

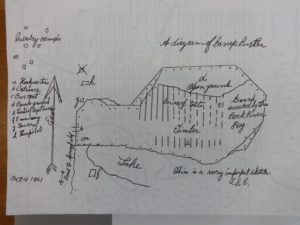

On October 4, 1861, Private Thomas Clingman of the 46th Infantry made in his diary this sketch map of Camp Butler.[4]

Private Clingman’s map shows the “rows of tents” where the soldiers slept just to the east of Clear Lake. (Note that east is toward the top in this orientation and north to the left.) The parade grounds are just to the east of the rows of tents. The cavalry portion of the camp was to the northeast, where there was more open ground for cavalry drilling and training.

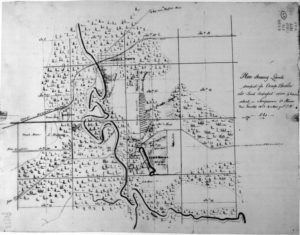

On November 25, 1861, (now) Corporal Clingman noted in his diary that “24 of our company were detailed to assist in building barracks.”[5] These new barracks were roughly two miles northwest of the original Camp Butler location on the east side of Clear Lake. Perhaps the main reason for the relocation was to put the camp close to the Great Western Railroad. By the end of December 1861, most Camp Butler soldiers were quartered in the new barracks. However, not all the details of the location transfer were worked out by that time. On January 8, 1862, Corporal Clingman noted that he “Went to the old camp with several of the boys after bread.”[6] Perhaps the bakery, then, was still located near Clear Lake.

This image shows the relative locations of the two camps.[7] Clear Lake looks like a leftward leaning “1” in the lower portion, and the original Camp Butler living quarters for the infantry were sited primarily just to the right (east) of the lake. The second location of Camp Butler is directly west of the two Sangamon River meanders, just at the bottom of the S-curve of the Great Western Railroad (area labeled “Barracks”). This is approximately where Camp Butler National Cemetery is today. Toward the top of this map is James Town – sometimes slangily mentioned as Jim Town – which is now named Riverton.

However, a broader reason for the relocation of Camp Butler was the growing realization, nationally, that the Civil War was not going to end in a few additional months. Thus, there was going to be a continuing need for Union troops, which started with recruitment and the transition from citizens to soldiers through training at places such as Camp Butler. In that light, Camp Butler needed barracks to protect against the weather and efficiencies in transportation that railways could provide (and that dusty or muddy roads could not).

[1] Illinois State Journal, July 31, 1861, p.3.

[2] Illinois State Journal, August 16, 1861.

[3] Illinois State Register, September 14, 1861.

[4] The Diary of Thomas Clingman and the Clingman Family Letters, typed manuscript at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, p. 19.

[5] The Diary of Thomas Clingman, p. 37.

[6] The Diary of Thomas Clingman, p. 46.

[7] The Diary of Thomas Clingman, p. 18, which has a partial replica of this image.

———————————————————————————————————————

Thanksgiving Proclamation (added 25 November 2020)

Did Illinois Civil War soldiers celebrate Thanksgiving?

Generally, yes. President Washington declared “Thursday the 26th day of November” (the same as this year) would be recognized as Thanksgiving Day (in 1789). U.S. presidents and governors intermittently gave recognition to Thanksgiving in the first half of the nineteenth century through various declarations and resolutions.

Officers Hospital No. 17, Memphis, Nashville, November 4, 1863, to wife, Anna

I wish I could get home for Thanksgiving I should enjoy it so much but it is impossible.

—Chaplain Hiram Roberts, 84th Infantry, Adams County

During the Civil War, in September 1863, President Lincoln was asked by Sara Josepha Hale “. . . to have the day of our annual Thanksgiving made a National and fixed Union Festival. . . .”[1] The end result was the following presidential proclamation written by Secretary of State William Seward and signed by Abraham Lincoln.

October 3, 1863

By the President of the United States of America.

A Proclamation.

The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God. In the midst of a civil war of unequalled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign States to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict; while that theatre has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union. Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defence, have not arrested the plough, the shuttle or the ship; the axe has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege and the battle-field; and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom. No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy. It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next,[2] as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity and Union.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Seal of the United States to be affixed.

[signed: Abraham Lincoln]

Done at the City of Washington, this Third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the Independence of the United States the Eighty-eighth. ABRAHAM LINCOLN

By the President:

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.[3]

Note that the above proclamation is not to be confused with President Lincoln’s other calls for a “thanksgiving.” Here is one example.

Memphis, Tennessee, May 1, 1863, to sister, Addie Tower

As yesterday was the day appointed by the President for thanks-giving, work of all kinds was laid aside for the day and most of the buisness houses were closed. by order of Gen Harlbut [Stephen A. Hurlbut] they were obliged to respect the day if they did not pray for the success of our army.

—Private John Cottle, 15th Infantry, McHenry County

Private Cottle’s statement likely was in reference to President Lincoln’s March 30, 1863, proclamation which reads, in part:

We have been the recipients of the choicest bounties of Heaven. We have been preserved, these many years, in peace and prosperity. We have grown in numbers, wealth and power, as no other nation has ever grown. But we have forgotten God. We have forgotten the gracious hand which preserved us in peace, and multiplied and enriched and strengthened us; and we have vainly imagined, in the deceitfulness of our hearts, that all these blessings were produced by some superior wisdom and virtue of our own. Intoxicated with unbroken success, we have become too self-sufficient to feel the necessity of redeeming and preserving grace, too proud to pray to the God that made us!

It behooves us then, to humble ourselves before the offended Power, to confess our national sins, and to pray for clemency and forgiveness.

Now, therefore, in compliance with the request, and fully concurring in the views of the Senate, I do, by this my proclamation, designate and set apart Thursday, the 30th. day of April, 1863, as a day of national humiliation, fasting and prayer. And I do hereby request all the People to abstain, on that day, from their ordinary secular pursuits, and to unite, at their several places of public worship and their respective homes, in keeping the day holy to the Lord, and devoted to the humble discharge of the religious duties proper to that solemn occasion.[4]

Rather, instead of a day of fasting, during the Civil War the holiday of Thanksgiving was associated with foods that would be familiar to us in the twenty-first century (albeit under very different national circumstances).

Officers Hospital at Memphis, Nashville, November 26, 1863, to wife, Anna

Thanksgiving day has come again I have been to church & back again & eaten dinner, not such a one as our good old New England tables used to groan under but still a very fair one for this region & especially for a hospital. For instance we had turkey boiled ham sweet & Irish potatoes pickles cake & pie. I doubt not I feel just as well as though I had had a thousand varieties & am certainly thankful that I have so much while thousands of others are destitute & even our brave boys who are fighting the battles of the Union have at the best only hard tack & side bacon I fear too that while we are thus enjoying the good things of life many of our soldiers are being torn with shot & shell ushered into eternity or maimed & crippled for life.

—Chaplain Hiram Roberts, 84th Infantry, Adams County

And to be clear, soldiers did not require President Lincoln’s 1863 national holiday proclamation to feast at Thanksgiving.

Danville, Kentucky, December 4, 1862, to sister

[For Thanksgiving] Well we had a most an allkilling big feast at one of the best union ladies house in the town of Danville [KY]. The boys got it up just how James can tell you better, but I can tell you what we had for I was there about that time. Wal [for “Well now . . .” perhaps] there was roast turkey stuffed nigh to bursting, mashed potatoes, loaf bread, corn bread, biscuit, pie, pickled tomatoes and beets, Blackberry-jam and last but not least the pleasure of sitting down to a table to eat a meal of victuals something I have not done since I left Waukegan.[5]

—Private John Y. Taylor, 96th Infantry, Lake County (younger brother of Corporal James M. Taylor)

Thus, well prior to 1863, Thanksgiving already had been a long-standing American holiday tradition.

[1] Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55), 6:497, first annotation.

[2] This day also was the 26th of November.

[3] Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–55), 6:496-7.

[4] Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 6:156. Proclamation Appointing a National Fast Day

[5] With thanks to Glenna Schroeder-Lein for some transcription details regarding this letter.

———————————————————————————————————————

Favorite soldiers (added 20 November 2020)

This is a theme I last addressed on 17 January 2020, albeit not very well. When being interviewed or answering questions live about the book, I often am asked who my favorite soldiers or letter writers are. Most recently, I received this question during a live interview last week.[1]

As a social scientist, I always chaff when trying to explain my sentiments because I realize my answers are not what most listeners are hoping to hear. Readers, however, have a prerogative to choose favorites in any way they see fit. As a latter-day ethnographer, of sorts, that is neither my role nor purpose.

In the interview last week so as to give an on-the-spot answer, I said the 165 soldiers in the book are my favorites because they made “the cut” out of all the publishable materials I had to work with at the time. Again, that is not a very satisfying statement for most people.

Here is how I would explain my perspective. When I was gathering materials that later turned into the current book, I was transcribing statements from soldiers’ personal letters at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. I had randomly selected those collections from the card catalogue. After about the first hundred collections or so, I began to retrospectively examine my sample for biases. That is, for example, in my collecting at that point was I over-representing officers or particular pay grades, was I covering Illinois geography evenly (by county and region), were all military branches represented, etc.? I discovered I needed to make some modest efforts to address a few deficiencies. One area my sample lacked, which I could not readily correct, was USCT enlisted soldiers.[2] This likely is due to low literacy rates among USCT soldiers. The one letter transcription I did find, in a commemorative volume to a commanding officer, seemed very much like it was written by someone else and the soldier only signed the letter. Ultimately, I could not verify that the soldier wrote the letter, plus it offered next-to-nothing about soldiering experiences. So, I did not include the soldier or the letter.

More briefly, are the soldiers featured in the book representative, or even a random sample, of all Illinois soldiers? No, likely not. More aptly described, it is an attempted even-handed sample of the Illinois soldiery that likely fails toward the edges (i.e., where numbers in the universe of Illinois Civil War soldiers are small).

What does sampling have to do with “favorites”?

All the soldiers’ letters from which I made transcriptions had something to say and offered a variety of perspectives. I had no a priori expectations or hypotheses as I wrote out my transcriptions. I was not looking for certain themes, motifs, types of descriptions, etc. It was relatively easy for me to work in this tabula rasa mode because I was collecting ideas for a poetry project and not a history book. Then, in retrospect, I started to see common themes, subjects, and experiences. And, I should quickly add, I also began to pick out those that were rare or not the norm.

In the end when compiling the book, I let the soldiers’ writings determine the book’s content as much as possible. Collectively, if I had ten examples of soldiers describing picket duty, say, I selected just a few that fit well together and were understandable to a lay reader. That stated, I did not shy away from including soldiers who were phonetic spellers or had questionable grammar. (In fact, in some cases, those writers’ “voices” could be more easily heard coming off the pages.) In short, I tried to limit my biases and let the writers speak for themselves. And in that sense, I am very much the editor of this book and not its author.

Thus, my favorites were any soldier who had something to say that added to the understanding of their collective experiences, circumstances, or emotions.

[1] 12 November 2020, Illinois History Forum, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library; the interview can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IqanpKz0i7I

[2] USCT = U.S. Colored Troops, of which there were about 1,800 from Illinois.

———————————————————————————————————————

Mrs. Tilton of Springfield (added 13 November 2020)

On page 221 of the book, there is a soldier’s letter quotation describing meeting Mrs. Tilton who was the “lady of the house” at the Lincolns’ Springfield residence in May 1865. What else is known about Mrs. Tilton relative to the Civil War?

Here is that quotation.

Camp Butler, near Springfield, Illinois, May 25, 1865, to friend, Martha

we stayed all night at the Soldiers home a poor place in the morning Daniel McEawen & Edward Grow and I went over town went to the residence of Mr Lincoln the Lady of the house invited us in we had a long chat she played on the piano for us and when we went to go away she gave us some leaves and some flowers from the yard which I will send to you knowing That you are allways happy to receive such curiosities

—Private William Cochran, 102nd Infantry, Mercer County

In the book I explained that “Likely, ‘the Lady of the house’ was Mrs. Lucian Tilton. Her husband, the president of the Great Western Railroad, had an open-ended annual lease, which started in February 1861, to live in the Lincolns’ Springfield residence.”

The following is from the Lincoln Home National Park Service website.[1]

The Lincolns rented the house to the Lucian Tilton family when they left for Washington. As the Tiltons bought most of the Lincolns’ furniture, the house remained nearly unchanged inside and out for several years. However, they added to the kitchen. When Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, the Tiltons accommodated hundreds of mourners visiting the house, taking pictures, or snatching a leaf or a blade of grass from the lawn and trees. Mrs. Tilton had to ask for military protection around the house when people started taking paint off the clapboards and bricks from the retaining wall.

The Tiltons subsequently moved to Chicago in 1869.

While in Springfield during the Civil War, Mrs. Lucian (Lucretia) Tilton was active in the Ladies’ Springfield Soldiers’ Aid Society. In its annual report from August 1862, Mrs. Tilton was shown as the Secretary of the Society. Here are some highlights of the report describing the goals and accomplishments of the Society.

First Annual Report of the Ladies’ Springfield Soldiers Aid Society.[2]

August 28, 1862

But little more than a year has passed since our country was roused from dreams of peace and prosperity, by the outbreak of a most wicked rebellion, and slowly and reluctantly, by lessons taught at the cannon’s mouth, or traced in character of blood, has it been brought to realize the full magnitude of the contest in which it is thereby involved.

While men have nobly and unhesitatingly rushed by thousands, to rescue, from impending peril, a government rendered dearer than life itself by a long experience of its wisdom and beneficence, the women of the land, in a spirit of patriotism no less heroic, have bid them go forth, and though unable to share the dangers and privations incident to the soldier’s life, have followed them with prayers, breathed from lonely, aching hearts, and so far as is possible, with the home comforts so unselfishly cast aside. They feel that to sit with vitally folded hands, to be engrossed by pleasure and frivolity, or selfishly absorbed in the daily domestic and social routine, while husbands, sons and brothers are offering up their heart’s blood upon freedom’s altar, would prove them totally unworthy the enjoyment of the high and holy privileges secured at so terrible a cost.

Moved by sentiments like these, and belief in the greater efficiency of combined action, a few ladies in response to a notice given from the pulpits of the city, assembled in Cook’s Hall on 28 August, 1861, and decided to unite their efforts, in behalf of our brave volunteers, under the name of Ladies’ Springfield Soldiers’ Aid Society, the payment of $.25 constituting a membership. We commenced our labors in the belief that they would be required only a few months; that the dark cloud marching over the southern horizon, which we hoped to see speedily dispelled, has assumed more and more gigantic proportions until it pollutes with its baleful shadows every portion of our beloved country; and the close of our first anniversary begins with it the prospect of arduous unremitting toil for a long time to come.

In order to meet the frequent calls coming to us from hospitals where brave men are languishing from wounds or sickness, contracted in their country’s service, we have often found it necessary busily to ply our needles every day in the week, from morning till night, and to hold many evening meetings for the making of slippers and bandages. Though the society now numbers over 160 members, the average attendance has not exceeded 20 or 30.

. . .

In the hospitals at Camp Butler we have enjoyed the rare privilege of acquainting ourselves by personal observation, with the wants of Army hospitals generally, and of assuring ourselves that we are not laboring in vain. The tear of gratitude which has started to the eye of the sick soldier, as the wisp of straw beneath his aching head has been replaced by the soft pillow, and the earnest thanks which have greeted us for not forgetting those suffering far away from home and friends, have proved an ample compensation for all we have been able to accomplish, and far outweigh the many discouragements which have beset our path. Among them, and in the camp generally, we have distributed hundreds of books, magazines, tracts, newspapers, and quite a large number of Testaments, placed in our hands by the Springfield agent of the Sangamon County Bible Society. Books never failed to meet an eager welcome, and we are convinced that a vast amount of good might be accomplished could every Army hospital be supplied with the kind of reading best adapted at once to interest and instruct. We take pleasure in acknowledging the kindness of those gentlemen who have taken many articles from us to the hospitals, when we have been unable to visit them in person.

While feeling that the six soldiers in our immediate vicinity should ever claim our chief attention, we have not forgotten those far away, entering the year 29 boxes of supplies have been sent to the hospitals of Cairo, Bird’s Point, Mound City, Paducah, Cape Girardeau, Shawneetown, Keokuk, the St. Louis Sanitary Commission, the Mississippi Harbor fleet, and to the wounded upon the field immediately after the battles of Fort Donelson and Shiloh. The following articles were contained in these boxes or distributed at Camp Butler: 500 cotton shirts, three flannel shirts, 522 pair cotton drawers, 259 pair woolen socks, 122 pair cotton socks, 155 pair slippers, 23 calico wrappers, 20 pair mittens, 186 bed Sacks, 243 sheets, 255 feather pillows, nine moss pillows, 154 pillow ticks, 676 pillowcases, for blankets, 102 comfortables, 213 linen handkerchiefs, 576 towels, 11 curtains, eyeshades, 12 furnished needle books, 18 pincushions, 231 palm leaf fans, 2492 bandages, 13 boxes adhesive plaster, 24 pounds Castile soap, 190 pounds cornstarch in barley, furina tea, crackers, etc.; lint, sponges, pains, and linen; dried, canned, preserved and pickled fruits; jams, jellies, foreign and domestic wines and cordials. Of articles somewhat worn: 312 cotton shirts, six flannel shirts, 112 pair cotton drawers, 13 pair summer pantaloons, 19 summer coats, 21 comfortables, 13 sheets, 11 blankets, 234 towels and 76 pocket handkerchiefs.

In addition to this list we have furnished 146 articles of clothing for female nurses in the hospitals of Cairo, Paducah and elsewhere.

We close the year and responding to an urgent call from the surgeon of the Mississippi Harbor fleet for the supplies rendered necessary by the enlargement of the hospital boat to accommodate 50 more patients. This will nearly exhaust our treasury, but past experience has taught us to work hopefully on, trusting that generous friends will not fail us in time of need.

. . .

While praying that the blessings of peace may soon be vouchsafed to our now distracted country, but is resolved that so long as men must bleed and die upon the field of conflict, we too will be found, ever vigilant and faithful, at our allotted post of duty.

Respectfully submitted,

Mrs. L. Tilton, Sec.

Thus, it is no wonder that Mrs. Tilton was generous with her home and her time for a few random soldiers on the streets of Springfield in May 1865.

[1] https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/liho/houseTour.html

[2] As reprinted in the Illinois State Journal, September 11, 1862.

———————————————————————————————————————

October 1861 Alton Incident Addendum[1] (added 6 November 2020)

Since the previous posting on 30 October about the Alton incident involving the “Princeton Regiment,” there has been additional information that has come to my attention. Perhaps the most important piece is the following “order,” I will call it, regarding the recruitment of soldiers in Illinois, from the “Commander in Chief,” Illinois Governor Richard Yates.

State of Illinois

Head Quarters, Commander in Chief

Springfield October 23rd 1861.

While acknowledging the unity of interest which bind citizens of all loyal States in a common support of the Government a sense of State pride and the duties to be performed for the interests of this Commonwealth lead one to encourage all her patriotic sons who desire to take up arms for the Union, to attach themselves only to the forces of Illinois, and to aid them in this and enable the State to discharge her whole duty to the Federal Government – recruiting within the limits of this State for the military organizations of other States is hereby forbidden, and recruiting officers not representing companies or regiments organizing under orders from these Head Quarters are notified to withdraw immediately.

Rich. Yates

Governor[2]

(The bolding in my doing.)

It can well be imagined, given the date of this order and the occurrence of the Alton incident on October 29, that it may not have reached any military recruiters in Bureau County and, specifically, Colonel Winslow recruiting in Princeton, Illinois.

The following is from the History of Bureau County, Illinois, which chronicles Colonel Winslow’s recruitment saga.

F. Winslow received directly from the Secretary of War authority to raise a regiment, and established a camp at the fair grounds in Princeton, calling in several of the organized companies that had taken part in the 4th of July, and several from adjoining counties. Pending the organization of the regiment communications were had with Col. Berdan, who was raising a regiment of sharpshooters in St. Louis, and it was proposed that the Bureau Regiment should join them and form a brigade. The proposition was favorably entertained by all, from Col. Winslow to the drummer boys, and everything was working to that end. A steamboat was chartered to convey the command from De Pue to St. Louis, and on being notified of its arrival at De Pue orders were issued by Col. Winslow for the regiment to be readv to march early next morning. While all these movements were progressing other matters were attracting attention. Although the regiment was being formed under authority conferred upon Col. Winslow, and although there was a general understanding that he was to be the Colonel, it became evident during the weeks that he was in charge of the camp that most of the officers and a large portion of the men were not satisfied with the prospect of having him for Colonel. Perhaps any other man under the opportunity for criticism that a sort of trial period gave would have been equally unsatisfactory, but whether that be so or not it is certain that he became extremely unpopular, and it was rather an open secret about the time of leaving for St. Louis that probably it would not be Winslow that would be elected Colonel. It is presumable that Winslow did not realize this until the St. Louis movement had reached its climax, and until after he had ordered the march out of camp. On the Sunday morning appointed [probably October 27, 1861], at an early hour, he headed the march, and all went well until the public square was reached, when he ordered a halt, and proceeded to address the men, rather urging them that it would be better for all concerned not to go to St. Louis, but instead to march back to camp and think it over. His talk was not very pointed, and at a pause some one at the head of the column gave the order in a loud, clear voice, ” forward march! ” and as the troops were pointed toward the east the march was taken up, and Col. Winslow saw his men march off without him; still, however, under the orders issued by himself the night before, and not countermanded. He attempted to stop them by calling after them, but they did not hear him.

It was found that the telegraph would not work at Princeton, so a messenger was sent to Maiden, and the Governor appealed to to [sic] stop the runaways, as they were called. Up to this time there had been no objections made to enlistments in any State of men belonging to other States, and the proposition for a squad, company or regiment to go to another State to enlist caused no surprise nor raised any objection. But just at this time it began to be looked into somewhat as to what each State was doing toward its quotas under the calls for troops, and Gov. Yates ordered that no more Illinois men should go out of the State to enlist, and the order was fresh when our men were on their way to St. Louis. The circumstances were not fully explained to the Governor, and he ordered the party stopped at Alton, and when the boat hove in sight a cannon was fired for it to round to and land. The men mistook this for a salute of honor, and again cheered and shouted in great glee. What heroes they were already! And the boat whistled and steamed along in the current, and another and another gun were fired in front of it. At last a whizzing cannon ball plunged into the water just in front of the vessel. The transformation scene on the boat was instantaneous — the next shot would tear through it unless it promptly started toward land. ” And then there was hurrying to and fro, and whisperings of distress, and cheeks all pale that but a moment ago blushed at the sight of their own loveliness, ” and the boat started for the shore. The behavior of a single individual may serve as an index to the whole. A man who was accompanying the soldiers expecting to be Chaplain, had arrayed himself in a cocked hat and tall plumes, and looking like George Washington. He supposed the salute at first was in his exclusive honor, but when the tune changed and the solid facts of the case were realized, his hat was ofi” in a jifiy, the chicken feathers taken out and trampled under his feet, the cock taken out of his hat and he shrank back upon himself, and no Quaker ever was more a man of peace than was this erst Continental hero. The regiment was arrested the moment the boat landed, disarmed of their swords and guns, and they were headed for the old building of the Alton Penitentiary. . . .

This was a great surprise to all concerned, and a grievous disappointment. The men were soon ordered to Springfield, and after matters were explained to the Governor were relieved of any imputation of having attempted an improper act, for at the time they left Princeton none knew of the order against leaving the State. Shortly afterward they were sent to Chicago, and became a part of the Fifty-seventh Regiment. Col. Winslow did not seem to be recognized as having any sort of claim upon the men by anyone. He perhaps expected that they would be sent back here, or that he would be ordered to resume his command, but his connection with them ended on that bright Sunday morning.[3]

(Again, the bolding is mine.)

From the above: “. . .when the boat hove in sight a cannon was fired for it to round to and land. The men mistook this for a salute of honor, and again cheered and shouted in great glee. What heroes they were already!” This part of the description implies the recruits’ complete ignorance of the recent Governor Yates order. Did Winslow and the other officers onboard realize their intention to go to St. Louis to enlist the men was potentially in violation of that order? It seems “probably not.”

The following two regimental histories for the 57th Illinois Infantry also contain parts of the “Princeton Regiment” story.

HISTORY OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH INFANTRY.

The Fifty-seventh Illinois Infantry was recruited from various portions of the State, during the autumn of 1861, under the call of President Lincoln for 300.000 troops. Company A was enlisted with headquarters at Mendota; companies C, E, G and I with rendezvous at Chicago. These five companies, with other fragments, became quartered at Camp Douglas under Silas D. Baldwin, and were designated as the Fifty-seventh Regiment. Companies B, F, H and K were recruited in Bureau county, and in the early part of September went into quarters at Camp Bureau, near Princeton, under authority of Governor Yates granted to R. F. Winslow, of Princeton, to recruit a Regiment to be known as the Fifty-sixth Infantry. Company D. composed wholly of Swedes, was recruited at Bishop Hill, in Henry county, and joined under Winslow at Princeton. These companies, with one other,—which subsequently became a part of the Forty-fifth Illinois Infantry—went to Springfield in October by order of Governor Yates, and from there were sent to Camp Douglas, in the southern part of the City of Chicago, under F. J. Hurlbut. These two parts of Regiments (the Fifty-sixth and Fifty-seventh) were consolidated in December, and on the 26th day of the month were mustered into the United States Service as the Fifty-seventh Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry, with S. D. Baldwin as Colonel; F. J. Hurlbut, Lieutenant Colonel; N. B. Page, Major; N. E. Hahn, Adjutant: E. Hamilton, Quartermaster; J. R. Zearing. Surgeon, and H. S. Blood. First Assistant Surgeon— the chaplaincy being vacant. February 8, 1862, the Regiment, with about 975 enlisted men, fully officered, armed with old Harper’s Ferry muskets altered from flint-locks, and com- manded by Col. Baldwin, left Camp Douglas over the Illinois Central Railroad, under orders for Cairo. ILL., where it arrived on the evening of the 9th, thence direct by the steamer Minnehaha, to Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River, which had been evacuated by the enemy and taken possession of by our forces.[4]

In the above, “went to Springfield in October by Order of Governor Yates,” while technically true, sidesteps the incident at Alton and the recruits being made prisoners in getting to Springfield. Another history for the regiment simplifies its organization even more.

HISTORY OF THE 57th ILLINOIS.

The organization of the 57th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry was commenced in Chicago, ILL., Sept. 24, 1861, at Camp Douglas, by Col. S. D. Baldwin. At the same time, the 56th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry was perfecting its organization in Camp Bureau, at Princeton, ILL., under the command of Colonel Winslow. Governor Yates, of Illinois, ordered, the 56th Regiment to report to Camp Douglas, Chicago. Troops being needed at the front, and neither of the above organizations being perfect, having only five companies each, Governor Yates ordered a consolidation of the two, and they were mustered into the United States service Dec. 26, 1861, as the 57th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry, and numbered 1025 men.[5]

In summary, a combination of miscommunication or missing orders and perhaps a dissatisfaction among some or many of the recruits raised at Princeton resulted in the stopping of the steamboat Jacob Musselman at Alton. As far as can be ascertained, no charges were filed against Winslow regarding this incident.

[1] A gold star goes to Glenna Schroeder-Lein for the “Chronicling Illinois” reference regarding the Yates papers from the Wabash collection. Two gold stars to Robert I. Girardi for finding the pertinent bits in the History of Bureau County and pointing out the relevant Illinois infantry histories. Both of these scholars made this addendum possible and to them I give my sincere thanks.

[2] http://alplm-cdi.com/chroniclingillinois/items/show/20270

[3] H. C. Bradsby (ed.), History of Bureau County, Illinois (Chicago: World Publishing Co., 1885), 348-50.

[4] Reece, Brigadier General J. N. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois. Reports for the years 1861–1866, revised edition, vols. 1–8 (Springfield, IL: Phillips Bros., 1900), 4:66.

[5] William W. Cluett, History of the 57th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry (Princeton, IL: T. P. Streeter, 1886), 5.

———————————————————————————————————————

October 1861 Alton Incident (added 30 October 2020)

Were there any Civil War battles in Illinois?

No, there were not. There certainly were isolated guerrilla incidents and some small-scale, local incursions.[1] However, there were a few instances, especially early in the war, where projectiles were directed in warning at suspected Confederate-sympathizing vessels on the Mississippi River, along Illinois’s western border. Some of these occurred at Cairo, where, at Fort Defiance, for example, cannons were put in place to stop boats heading south to inspect if they were carrying goods to aid the Confederacy’s war efforts.

Cairo, Illinois, April 7, 1864, to friend, Mr. Tailor Ridgway

there was a big boat tried to run by here yesterday with contraband goods on her and our boys got in to the fort and opened a sixty four pound cannon on her and I tell you she bawled they shot at her three times and she came to shore a howling. and they arrested her captain and put him in the guard house. that is what a fellow gets for trying to be a rebel, to his country. there is a great many boats runing now and they are doing a big business.

—Corporal Jeremiah Butcher, 122nd Infantry, Macoupin County

In 1861, apparently there was a sort of Illinois “recruitment war” with Missouri. This is the 159th anniversary of an incident at Alton, Illinois, that resulted in imprisoning about 300 men, albeit not Confederates and merely potential Union volunteers.

Military Excitement.—Our citizens were somewhat astonished this morning to find our levee in possession of a detachment of troops from Camp Butler, who had come down during the night. They had planted a cannon on the levee, and thus established a blockade. Their purpose was to intercept and stop some 400 troops who becoming dissatisfied with matters in their camp, somewhere in the northern part of the state, had started off for Missouri via the Illinois River. One or two boats were stopped in the morning, but no runaways being found, they were allowed to proceed.

At about half past ten, however, the looked for boat appeared having in tow a barge loaded with soldiers. She was greeted with two blank cartridges, to which no attention was paid. A ball was then fired which struck the bow of the barge, damaging it somewhat. This being rather too close work, she rounded to and the entire party of military passengers were taken prisoners. The officers, in command were required to deliver up their swords and, after some delay, both officers and men were marched under guard, into the old Penitentiary, where at the time of writing this, they remain.[2]

A newly-promoted corporal at Camp Butler wrote a letter to friends at home (as well as making personal diary entries) that described his regiment’s involvement in stopping and seizing potential volunteer soldiers headed to perhaps St. Louis, Missouri, by way of the Mississippi River.

Camp Butler, near Springfield, Illinois, October 31, 1861, to sister, Eliza

About 12 oclock on Monday night our regiment received orders to pack knapsacks and get ready for an amediate march to Jimtown, the nearest station on the Springfield railroad. We were soon ready and in one hour and fifteen minutes from the roll of the drum we were at the station. There 250 men were taken from the regiment and the rest sent back to camp. We amediately got aboard the train which was in readiness and started westward, no one knew where or for what purpose except, perhaps, the officers. Several artilerists accompanied us with a brass six pounder.

A few miles beyond Springfield, at the junction, we changed cars to the Chicago, Alton and St. Louis Rail Road and continued in a westward direction, arriving at Alton about daybreak. Here I had a view of the Mississippi for the first time. Two large steamboats were lying at the wharf at the time and were quite a sight to me, having never seen one before. After we had dismounted from the cars and had formed in line on the river back, 20 rounds of cartridges were given to each man. An Enfield Rifled Musket was then given to each man; these were loaded and stacked on the river bank. The object of the expedition now became known to us. Some troops which were in camp at Princ[e]ton in this state, becoming dissatisfied, had started down the river on a steamer for some place in Missouri to join a regiment of sharpshooters in that state. The Governor determined to stop them and it was for this purpose that we were at Alton.

Several men were placed on a high bluff overlooking the river who were to give the signal of the boats approaching by raising a flag. About 11 oclock the flag was raised and we were soon in ranks ready to give them a volly if it should be necessary to do so. As the boat approached the town two blank cartridges from the six pounder were fired at her. This failing to bring here [her] to shore, a ball was next fired striking her on the bow. This brought her to the wharf where she was fastened. No one was injured by the 3rd shot, but it [was] said that had the ball struck the boat a foot or two higher it must have killed several. Colonel Davis with a squad of men now went on board and demanded that the officers should give up their swords which they did. The men, about 300 I think, were then taken to the old penitentiary where they remained until 10 oclock in the evening when we started with them for Camp Butler which we reached about 4 oclock the next morning. During the day we were exposed to a cold, piercing wind with clouds of sand and dust making it very disagreable. I do not know what will be done with the prisoners. We will know perhaps in a few days. There in less than 28 hours after we left camp we were back again having traveled over 150 miles.

—Corporal Thomas Clingman, 46th Infantry, Stephenson County

Subsequently, in the Springfield newspapers, there appeared statements – pro and con – concerning the nature of how volunteer soldiers in Illinois were recruited to fill regiments. Here is part of one of the articles.

We published yesterday a statement made by Messrs. Thompson and others, in reference to the affair of the Princeton Regiment, arrested for mutiny on board the Jacob Mussleman at Alton. We give today a counter statement by Col. Winslow, by whom the Regiment was raised. We do not see what advantage can result to either party by parading the matter in the newspapers; but as we have let one side have it say, we deem it no more than justice to allow the other the same opportunity. Our space, however, is not equal to an extended warfare of words, and we shall here shut down on any further publications. The trouble must be settled by the governor, and the parties in interest will please submit their grievances to him. We shall make no comment upon the communications which have been published, further than to say that they give an inside view of the manner in which the independent recruiting business has been carried on in this state, which is quite refreshing. In this light, if in no other, Col. Winslow’s statement will be found interesting.[3]

Suffice it to say the Thompson et al. and the Winslow statements are of “the one said/the other said” variety, involving promises made by a number of parties, including Missouri interests, and expectations not met. Were the actions by the “Princeton Regiment” individuals treasonous? Probably not, unless their intentions were to join a Confederate regiment in Missouri, which does not appear to be the case.

The following is not directly related to the “Alton affair” (even if the timing might suggest otherwise), but it does highlight a complication when Illinois soldiers join, en masse, out-of-state regiments.

Springfield, Illinois, October 31, 1861, to “His Ex’y Gov. Yates:”

Dear Sir: I was one of the many Illinois men who raised men in this State to carry to Missouri to give a prestige to Unionism there; and one of the many swindled out of a command to make place for St. Louis aspirants. Of the sixth Reg’t, to which I belonged, 9-10ths of the men are Illinoisans, and yet the whole of the staff and 9 of the 10 captains are St. Louis men. Sick of the scramble for shoulder straps, I joined Capt. Burnap’s Cavalry as a private . . .

—former Private Charles L. Wheeler, Burnap’s Cavalry, Missouri (Union)

Around this same time, Illinois Governor Yates did accept companies from other states to serve in Illinois regiments. This was at a time when states were generally meeting federal quotas for enlisting soldiers. It is worth noting that Illinois officials, regarding subsequent federal calls for soldiers, argued that previous overages enlisted during this period should be counted as part of Illinois’s required contributions. Here is an example.

Springfield, Illinois, August 21, 1862, to “Hon. E. M. Stanton”

It is now evident that Illinois on the 22d will have 50,000 enrolled volunteers for three-years’ service. Please inform me fully whether for excess of quota the State is to have credit for the number required for old regiments now in the field, and also what is expected of us in such case as to drafting.

Richard Yates, Gov. of Illinois

Meanwhile in November 1861, the Princeton Regiment men were held at Camp Butler (near Clear Lake), which at that time had little in the way of permanent structures. Corporal Clingman noted in his diary on November 9, 1861 that: “Our ’Alton prisoners’ left camp for Chicago this morning. After they had gone, myself with five others from our company assisted in taking down the tents that they occupied while here.”

[1] See Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), regarding a few Illinois examples.

[2] “Military Excitement,” Alton Telegraph (Alton, Illinois), November 1, 1861, p. 3.

[3] “The Princeton Regiment Again,” Illinois State Journal (Springfield), November 1, 1861, p. 2.

———————————————————————————————————————

Springfield’s Camp Yates (added 23 October 2020)

In the book, there are a few mentions of Camp Yates in Springfield. How big was Camp Yates and how much was it utilized during the Civil War?

[Editor’s note: This post contains some additional information from the previous post on Camp Yates in December 2019.]

On page 94, there is a brief quotation from Private William Clarke who wrote from an aging Camp Yates. Below is the full letter, which illustrates some of the latter-day characteristics of Camp Yates.

May 1st 1864 Camp Yates Springfield Illinois

Dear Father and Mother

I take my pen in hand to let you know how I am I am well at present in every respect my leg feels as well as it ever did. I hope this will find you all better health than I left you. I am doing very well here this time I get all I can eat of prety good grub we have A decent table to eat of of and decent grub to eat of it we have plenty beef boild and fried we have potatoes and warm bread. tea and Coffee and sugar and vegtable soup and Chairs to sit on while we eat we have allso good beds to sleep on in the Hospital. there is no ketchin desease here except the Mumps and Irresiples and Measles there has two died here since I come here I am not in the Hospital mutch except at night I help in the cook house some but most of the time I am scouting around through the country runing about Springfield with no control guard to cheer and no guards to pass to get in and out of Camp there is but one guard in camp and he is at the gate most all the fence around camp has bin tore down by the 8th Cavelry but all the Troops have left here except the Convalescents and A few sick the sutler is broke up and gone. the Magor is gone to Camp Butler and A familey lives in his office Lieutenant Elliot has gone to his Regiment his office is shut up so is the post office the Barricks are deserted and so is the Hospital that I was in before there is not one Corperal to be found in Camp the only places that is inhabited is the Hospital the Cook house Doctors office and the guard House the guard House is full of Copperheads that was taken at Charleston Coles County they are doomed to be executed as A warning to other Copperheads to show them how weak and foolish it is to try to resist the Goverment. the Ladies furnish us plenty of Books Magazines and News papers to read; Sunday one of my Comrads and me went to Springfield to Presbiterian Church, in the afternoon the Young Missionaries and Tract distributers Come through the hospital distributen Tracts and Sunday School Advocates and Repositaves they were from eight to 14 years old I guees I mean the Boys not the papers. it is A good thing I took some monney with me for I have not drawed anny yet but expect to shortly I have not had A chance to have any likenesses taken yet when I do I will send Marys to you and you can send it to her I want you to write to me immediately and let me know how you all are and let me know wether you have heard from Mary yet and send me the letter I wrote to Mary Elen you will find it in the History of the World and send me the directions to her and to Cousin Sarah and Uncle Michael, and if there is any letters come there for me I wish you would please put it inside of another Envelope and send it to me

No more at present

From your affectionate Son

William R. Clarke

—Private William Clarke, 8th Cavalry, Pike County

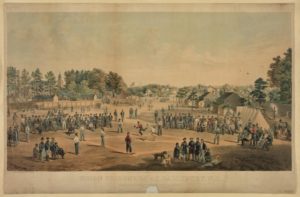

Like so many temporary mustering camps, Camp Yates essentially was the result of commandeering the local fairgrounds. At the time, those fairgrounds were on the western edge of Springfield. Today, that area is bound by Washington Street (N), Governor Street (S), Lincoln Avenue (W), and Douglas Avenue (E), which is roughly 1,400’ by 600’ or about 19.25 acres. As a point of comparison, Civil War Camp Butler (at its final location) was about 40 acres, 15 of which was for Confederate prisoners of war in 1862-63.

Most of these temporary mustering camps were closed by 1862, as Camp Douglas (then, near Chicago) and Camp Butler (near Springfield) were designated as the two main “camps of instruction” in Illinois. However, Camp Yates lingered on, perhaps because it was politically difficult to decommission something in the capital city named after the sitting governor.

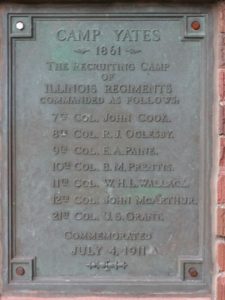

Private Clarke wrote “the Magor is gone to Camp Butler and A familey lives in his office.” He probably is referring to Major James J. Heffernan, the former Camp Yates commandant, who left in April 1864 to fill that same post at Camp Butler, replacing Lieutenant Colonel Reuben L. Sidwell (of the 108th Illinois Infantry Regiment). “A familey lives in his office” possibly may refer to the same building then-Colonel Ulysses S. Grant occupied in June and early 1861 while in charge of the 21st Illinois Infantry Regiment at Camp Yates. A plaque in the west wall of the current Dubois Elementary School on South Lincoln Avenue in Springfield lists the regiments who were at Camp Yates.

Below, this stone commemorative marker, originally placed near the corner of Douglas and Governor streets in 1909, was moved to the Dubois Elementary School west grounds.